Tematem kilkunastu tekstów zebranych w tej książce – spośród których część nigdy dotąd nie była publikowana – jest ludzki lęk przed śmiercią, a także możliwość opanowania tego lęku, stawienia mu czoła. To bardzo zróżnicowane teksty, pokazujące wszechstronność Kołakowskiego jako myśliciela, jak również jego głęboko ludzkie oblicze. Z równym zaangażowaniem i przenikliwością pisze filozof erudycyjny esej i list do nastoletniej czytelniczki, analizuje wielkie biblijne opowieści i wspomina tragicznie zmarłego przyjaciela. Wobec pytań o sprawy ostateczne, sens życia i śmierci, zawsze jesteśmy samotni. A jednak wielkość Kołakowskiego polega i na tym, że staje on wobec nich razem z czytelnikiem, obok niego. Nie w pozycji nauczyciela, ale jako towarzysz w poszukiwaniach. I choć jego myśl w swojej ostrości bywa bezlitosna – odsłaniając tę prawdę, że żyjemy w świecie obojętnym, pełnym cierpienia, pozbawionym łaski – jest zarazem pokrzepiająca. Pokazuje bowiem, że nawet w takim świecie można ocalić człowieczeństwo.

Leszek Kołakowski Book order (chronological)

A distinguished Polish philosopher and historian of ideas, known for his incisive critical analysis of Marxist thought and his later focus on religious questions. His work emphasizes learning history to understand who we are, rather than how to behave or succeed. In Poland, he is revered not only as an intellectual but also as an icon of opposition to communism. He has been described as a "thinker for our time," whose arguments, though critical, were presented in a way that respected intellectual opponents.

Główne nurty marksizmu Tom 2

- 542 pages

- 19 hours of reading

Tom 2 klasycznego już 3-tomowego dzieła o charakterze podręcznikowym. Jest uporządkowaną i bogatą w informacje prezentacją historii marksizmu. Autor śledzi źródła konstytutywnych pojęć marksizmu, ukazując wszystkie konteksty od starożytnych po współczesne. Zakorzenia myśl marksowską i marksistowską w europejskiej kulturze i filozofii, w zależności od potrzeb przechodzi od perspektywy ogólnej do interesujących szczegółów. Analizuje poszczególne odłamy i doktrynalne niuanse marksizmu.

Nowe wydanie najważniejszego i największego dzieła Autora. Książka została opatrzona wstępem Krzysztofa Pomiana, przyjaciela i ucznia Profesora. Tom 1 klasycznego już 3-tomowego dzieła o charakterze podręcznikowym. Jest uporządkowaną i bogatą w informacje prezentacją historii marksizmu. Autor śledzi źródła konstytutywnych pojęć marksizmu, ukazując wszystkie konteksty od starożytnych po współczesne. Zakorzenia myśl marksowską i marksistowską w europejskiej kulturze i filozofii, w zależności od potrzeb przechodzi od perspektywy ogólnej do interesujących szczegółów. Analizuje poszczególne odłamy i doktrynalne niuanse marksizmu.

Jednostka i nieskończoność to opowieść o Baruchu Spinozie, pierwszy wyraz fascynacji Leszka Kołakowskiego wiekiem XVII. Pasji tej Profesor pozostał wierny do końca życia, a do książki o Spinozie wrócił niedługo przed śmiercią, dyktując poprawki i uzupełnienia. Spinoza był dla niego od początku najważniejszym filozofem i główną inspiracją. Niewznawiana przez pół wieku pierwsza – i zarazem ostatnia, nad którą pracował – książka to nie tylko pamiątka po „wczesnym Kołakowskim”, ale dojrzała interpretacja, napisana z wnikliwością i charakterystyczną dla autora klarownością. Kołakowski dostrzega w metafizycznych wywodach Spinozy realne ludzkie problemy, odnosi to, co pozornie abstrakcyjne, do konkretu życia. Dzięki temu wykład o jednym z najtrudniejszych filozofów w dziejach staje się przystępny i aktualny. Praca dla miłośników Leszka Kołakowskiego i jedynej w swoim rodzaju filozofii XVII wieku.

Zbiór esejów z przełomu lat pięćdziesiątych i sześćdziesiątych ubiegłego wieku. Rozważania dotyczą klasycznych problemów filozoficznych i podstawowych pojęć, wokół których organizuje się specyficznie ludzka działalność człowieka - ów naddatek ludzkich sił i energii dający w efekcie tzw. kulturę. Istota filozofii, natura prawdy, mechanizmy i typy osobowości, problem decyzji, autorytetu, religii, wreszcie pytanie, w jakimś sensie autoironiczne, o znaczenie humanistyki i humanistów - to zagadnienia, które Autor bada ze swobodą i zainteresowaniem wytrawnego filozofa i historyka. Dla czytelnika uderzający jest widoczny w tych wczesnych tekstach szczery szacunek dla myśli Marksa, oparty na dogłębnej lekturze i prawdziwym zrozumieniu, oraz niechęć do wszelkich upraszczających interpretacji Marksowskiej filozofii. A właściwie szerzej: wspólnym mianownikiem esejów jest odrzucenie niesamodzielności myślowej, banalności w refleksji, urzeczawiającego i abstrakcyjnego podejścia do świata i życia. Książka stanowi krytykę powierzchownego myślenia i poprzestawania na grubych podziałach - jest wyrazem fascynacji złożonością świata i bogactwem różnic. Niezwykle inspirująca i aktualna lektura.

Tom 3 klasycznego już 3-tomowego dzieła o charakterze podręcznikowym. Jest uporządkowaną i bogatą w informacje prezentacją historii marksizmu. Autor śledzi źródła konstytutywnych pojęć marksizmu, ukazując wszystkie konteksty od starożytnych po współczesne. Zakorzenia myśl marksowską i marksistowską w europejskiej kulturze i filozofii, w zależności od potrzeb przechodzi od perspektywy ogólnej do interesujących szczegółów. Analizuje poszczególne odłamy i doktrynalne niuanse marksizmu.

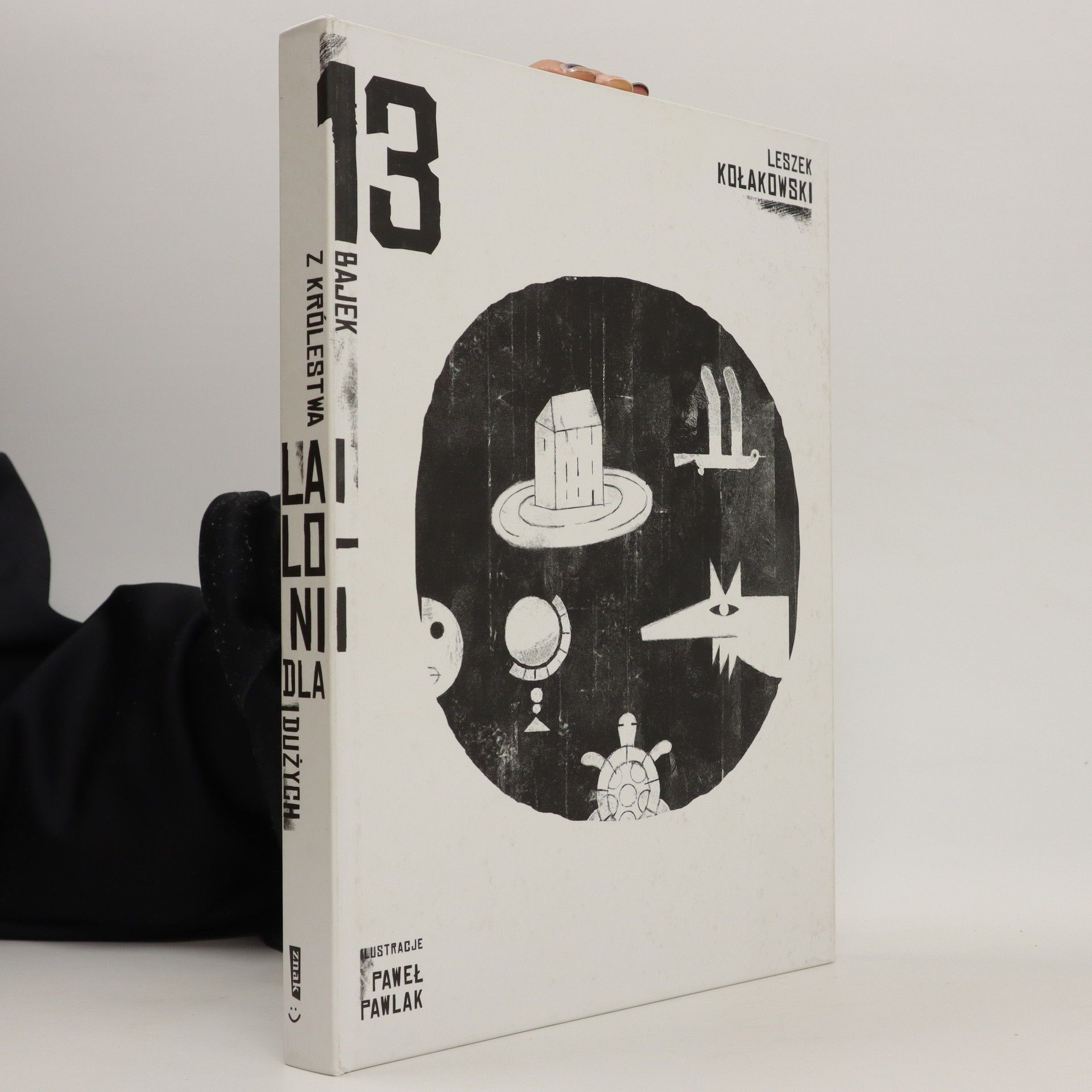

„Teraz jesteśmy już bardzo starzy. Na pewno nigdy nie dowiemy się, gdzie leży Lailonia, i na pewno nigdy jej nie zobaczymy. Być może jednak ktoś z was będzie miał więcej szczęścia, może komuś uda się trafić kiedyś do Lailonii. Jadąc tam, oddajcie w naszym imieniu kwiatek nasturcji królowej Lailonii i powiedzcie jej, jak bardzo chcieliśmy się tam dostać i jak nam się to nie udało.” To przedziwne, zaskakujące i napisane z wyjątkowym poczuciem humoru bajki „dla dużych i małych”. Można je odczytywać na wielu poziomach, dzieci odnajdą tu swoją Nibylandię, a dorośli Lailonię. Tekst uzupełniają piękne ilustracje autorstwa znakomitego grafika Pawła Pawlaka, który również opracował książkę typograficznie. Treść i forma na najwyższym poziomie.

Is God Happy?

- 328 pages

- 12 hours of reading

Features essays about communism and socialism, the problem of evil, Erasmus and the reform of the Church, reason and truth, and whether God is happy. This book deals with some of the eternal problems of philosophy and the most vital questions of our age.

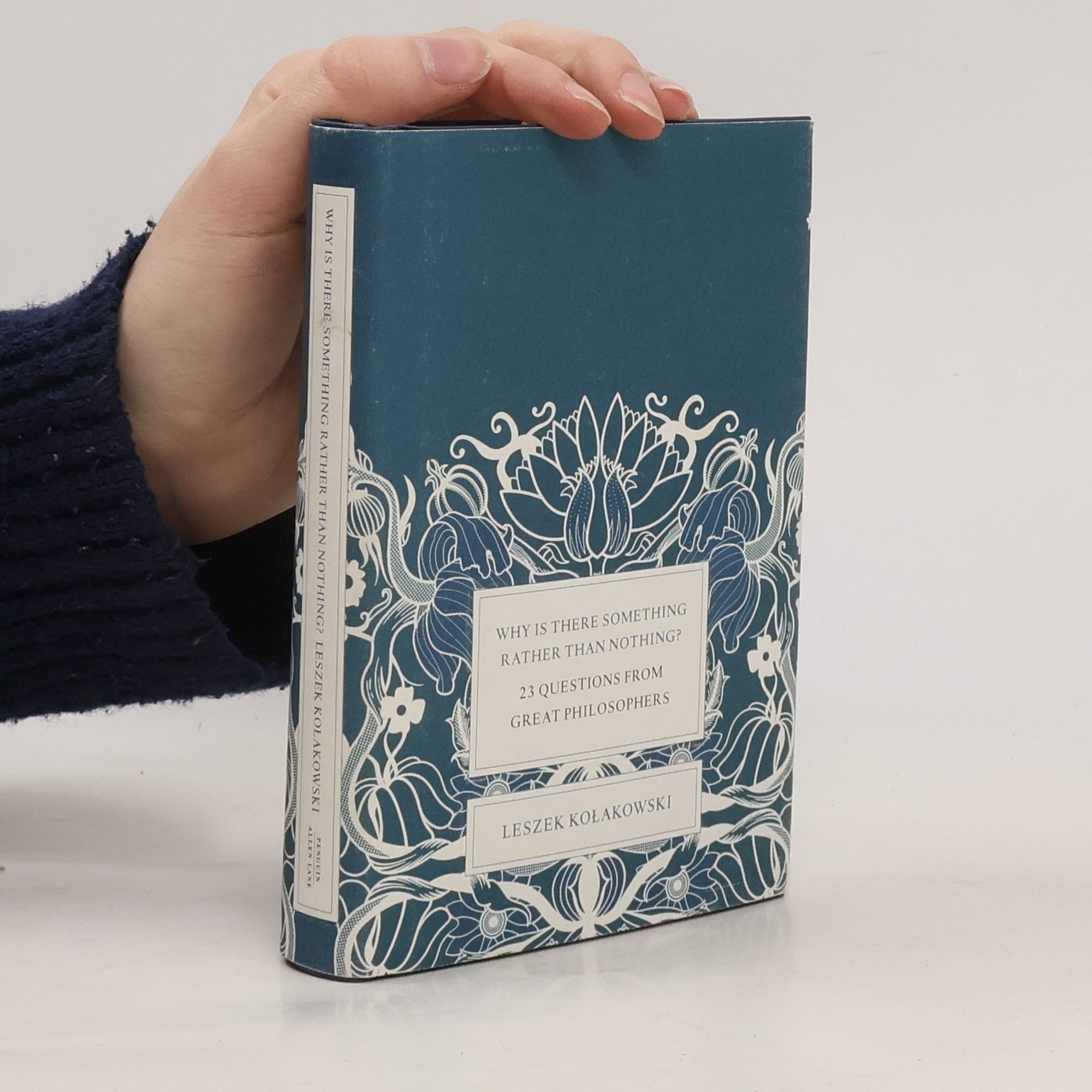

Why Is There Something Rather Than Nothing?

23 Questions From Great Philosophers

- 222 pages

- 8 hours of reading

Can nature make us happy? How can we know anything? What is justice? Why is there evil in the world? What is the source of truth? Is it possible for God not to exist? Can we really believe what we see? There are questions that have intrigued the world's great thinkers over the ages, which still touch a chord in all of us today. They are questions that can teach us about the way we live, work, relate to each other and see the world. Here Leszek Kolakowski explores the essence of these ideas, introducing figures from Socrates to Thomas Aquinas, Descartes to Nietzsche, and concentrating on one single important philosophical question from each of them. Whether reflecting on good and evil, truth and beauty, faith and the soul, or free will and consciousness, Leszek Kolakowski shows that these timeless ideas remain at the very core of our existence.