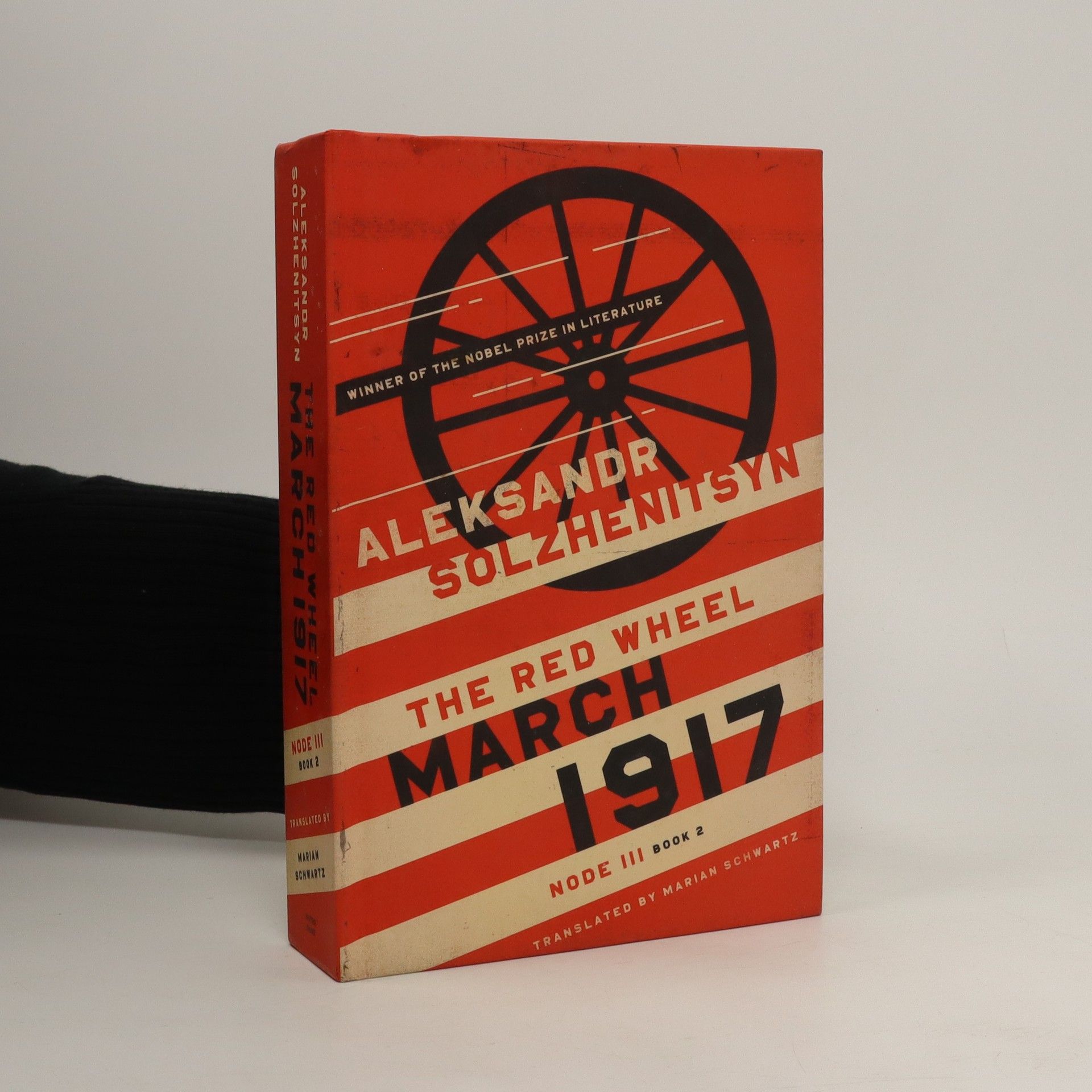

Set against the backdrop of March 1917, the narrative explores the revolutionary turmoil emanating from Petrograd, which significantly impacts the front lines of World War I. The story delves into the forces contributing to Russia's impending collapse, highlighting the chaotic intersection of war and revolution. Themes of disintegration and the struggle for power are woven throughout, capturing a pivotal moment in Russian history.

Alexander Issajewitsch Solschenizyn Books

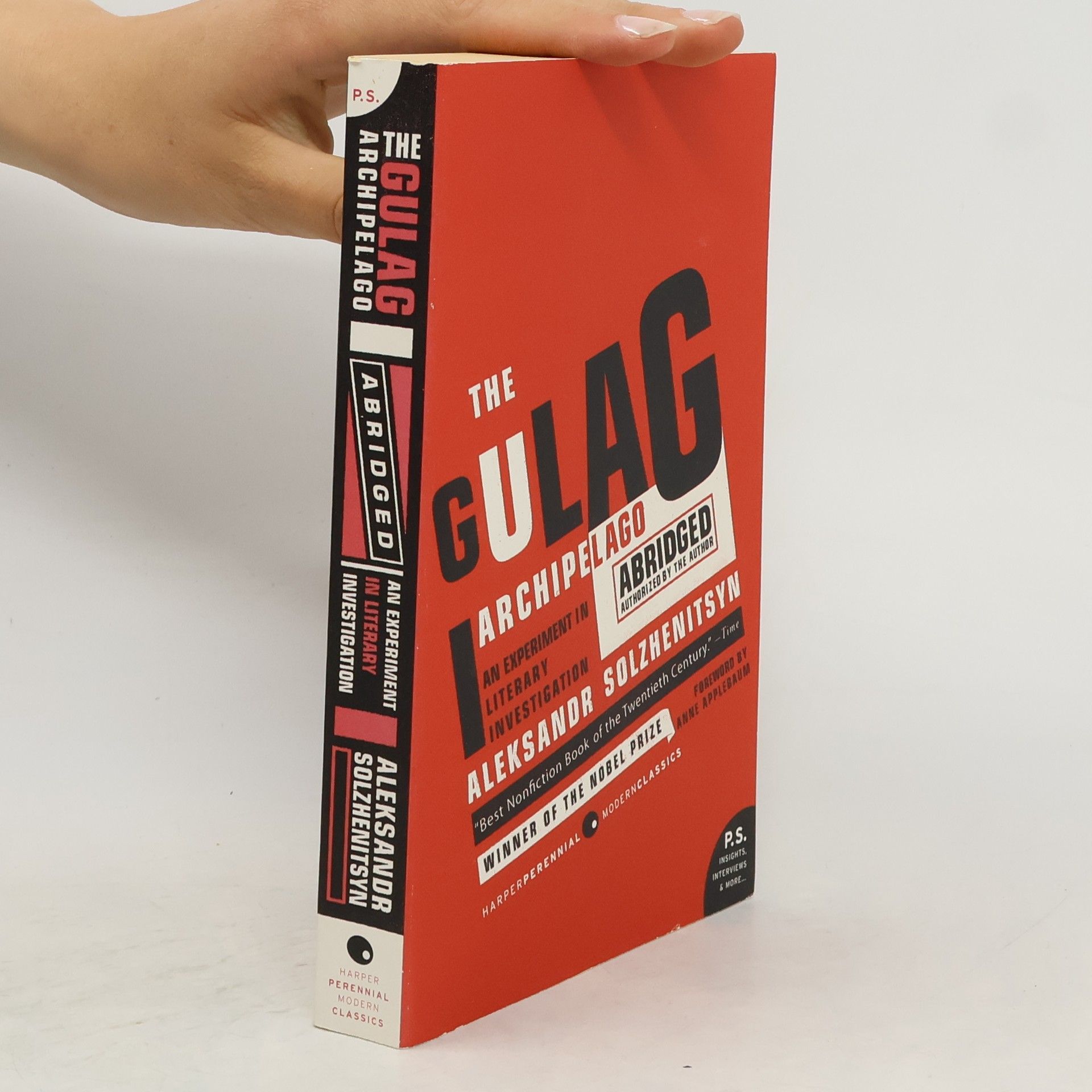

Alexander Issayevich Solzhenitsyn [səlʐɨˈnʲitsɨn] (Russian Александр Исаевич Солженицын, wiss. transliteration Aleksandr Isaevič Solženicyn) was a Russian writer and critic of the system. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. His main literary work, The Gulag Archipelago, describes in detail the crimes of the Soviet Union's Stalinist regime in the exile and systematic murder of millions of people in the Gulag.

Drawing on his own experiences before, during, and after his 11 years of incarceration and exile, Solzhenitsyn reveals with torrential narrative and dramatic power the entire apparatus of Soviet repression. Through truly Shakespearean portraits of its victims, we encounter the secret police operations, the labor camps and prisons, the uprooting or extermination of whole populations. Yet we also witness astounding moral courage, the incorruptibility with which the occasional individual or a few scattered groups, all defenseless, endured brutality and degradation. Solzhenitsyn's genius has transmuted this grisly indictment into a literary miracle.

Part two of this trilogy, reveals the experience of the hard-labor camps in Soviet Russia.

March 1917

- 700 pages

- 25 hours of reading

Solzhenitsyn's magnum opus delves into the Russian Revolution through a meticulously researched historical novel enriched with contemporary newspaper headlines, street action fragments, and cinematic screenplay elements. The narrative unfolds in three key nodes: August 1914 and November 1916, which explore Russia's crises, revolutionary terrorism, and the missed opportunities of Pyotr Stolypin's reforms, culminating in the disillusionment of patriotism as World War I ravages the nation. The third node, March 1917, captures the essence of the Russian Revolution, detailing the collapse of the Imperial government amid mob violence and the opposition's inability to steer events. Set from March 8-12, the first book introduces over fifty characters during the tumultuous days when the Russian Empire begins to disintegrate. Bread riots in Petrograd escalate unchecked, leading to police casualties and army mutinies. The horrified anti-Tsarist bourgeoisie rush to claim provisional power, while socialists establish a Soviet to challenge their authority. Meanwhile, Emperor Nikolai II is away at military headquarters, leaving his wife, Aleksandra, isolated with their sick children. The stability of the Russian state hangs in the balance, drawing comparisons to Tolstoy's War and Peace, as both works aim to narrate an era's story with universal significance.

The book commemorates the centenary of the Russian Revolution through Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's epic narrative. It is part of "The Red Wheel" series and delves into the events of March 1917, offering a profound exploration of the historical and social upheavals during this pivotal time in Russian history. Solzhenitsyn's insights provide a deep understanding of the revolution's impact, reflecting on the complexities of human experience amid turmoil.

Cancer Ward examines the relationship of a group of people in the cancer ward of a provincial Soviet hospital in 1955, two years after Stalin's death. We see them under normal circumstances, and also reexamined at the eleventh hour of illness. Together they represent a remarkable cross-section of contemporary Russian characters and attitudes. The experiences of the central character, Oleg Kostoglotov, closely reflect the author's own: Solzhenitsyn himself became a patient in a cancer ward in the mid-1950s, on his release from a labor camp, and later recovered. Translated by Nicholas Bethell and David Burg.

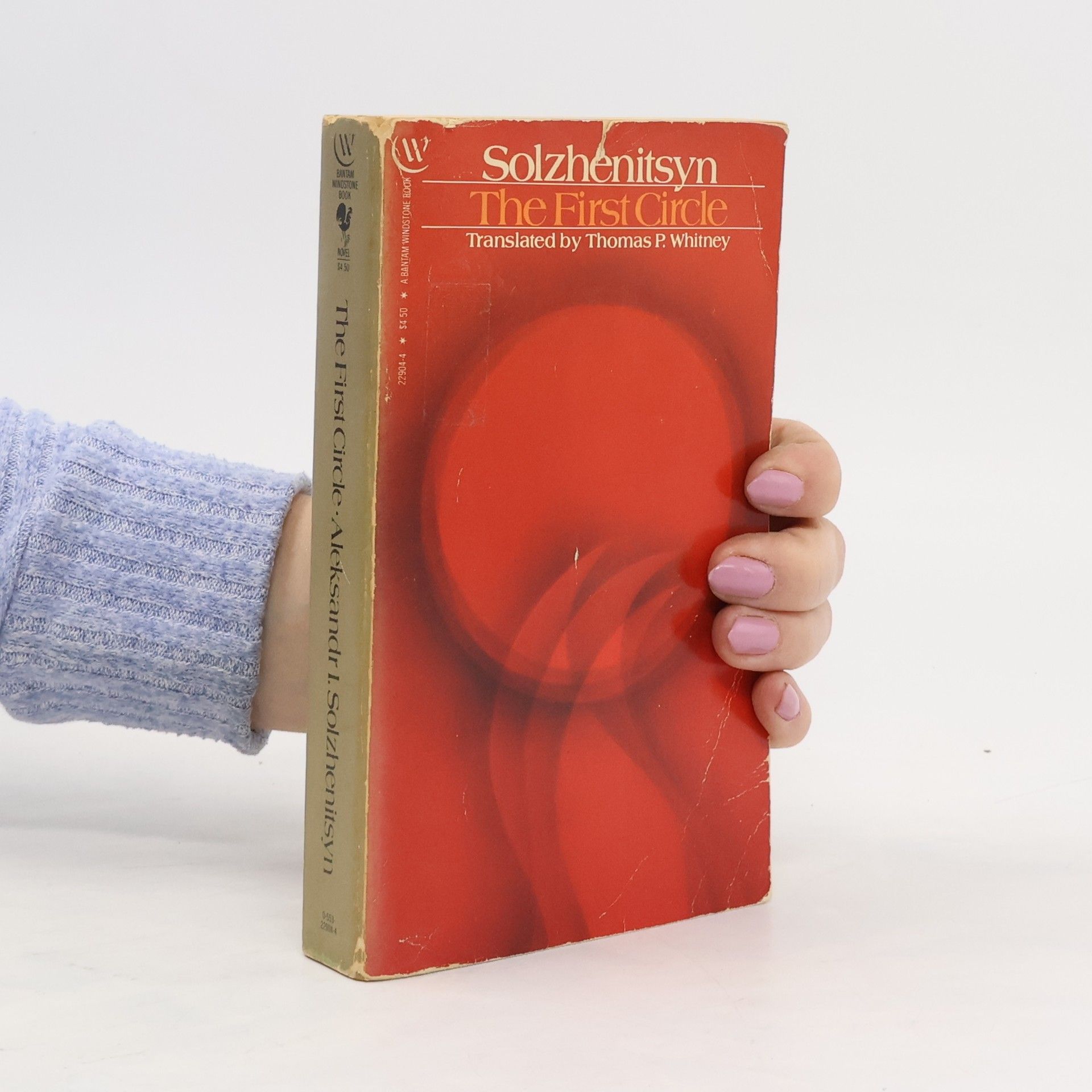

In the First Circle depicts the lives of the occupants of a sharashka (a research and development bureau made of GULAG inmates) located in the Moscow suburbs. This novel is highly autobiographical. Many of the prisoners (zeks) are technicians or academics who have been arrested under Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code in Joseph Stalin's purges following the Second World War. Unlike inhabitants of other gulag labor camps, the sharashka zeks were adequately fed and enjoyed good working conditions; however, if they found disfavor with the authorities, they could be instantly shipped to Siberia. The title is an allusion to Dante's first circle, or limbo of Hell in The Divine Comedy, wherein the philosophers of Greece, and other virtuous pagans, live in a walled green garden. They are unable to enter Heaven, as they were born before Christ, but enjoy a small space of relative freedom in the heart of Hell.

Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956 Abridged, The

- 528 pages

- 19 hours of reading

Describes individual escapes and attempted escapes from Stalin's camps.

The Mortal Danger

- 130 pages

- 5 hours of reading

Solzhenitsyn short piece on the Perils of misconceptions about Russia for America

Alexander Solzhenitsyn and six dissident colleagues who at the time of publication were still living in the USSR — six men totally vulnerable to arrest, imprisonment, or execution by the Soviet authorities — joined in the midseventies to write a book which surely remains the most extraordinary debate of a nation’s future published in modern times. Shattering a half-century of silence, From Under the Rubble constitutes a devastating attack on the Soviet regime, a moral indictment of the liberal West, and a Christian manifesto calling for a new society — one whose dominant values would be spiritual rather than economic. Personally edited by the Nobel Prize-winning author, fired by his own substantial contributions, From Under the Rubble articulates Solzhenitsyn’s most fervent call to action. His daring, and the remarkable courage of his colleagues, is testament to the seriousness of their demand for a revolution in which one does not kill one’s enemies, but in which “one puts oneself in danger for the sake of the nation!” With an introduction by Max Hayward, and translated under the direction of Michael Scammell. The contributors: Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Mikhail Agursky, Evgeny Barabanov, Vadim Borisov, F. Korsakov, A.B., Igor Shafarevich.