The Stone World

- 240 pages

- 9 hours of reading

Depicts an American boy's childhood in Mexico, ensconced in a world comprised of communist European exiles, local union activists, street children and avant-garde artists like Frida Kahlo

Friedrich Dürrenmatt was a Swiss dramatist and prose writer whose work deeply reflected the recent experiences of World War II. A proponent of epic theatre, he gained fame for his avant-garde dramas, philosophically profound crime novels, and often macabre satire. His writing explored the darker aspects of human nature and the absurdities of existence with a unique sense of dark humor. Dürrenmatt grappled with themes of guilt, justice, and morality in a volatile world.

Depicts an American boy's childhood in Mexico, ensconced in a world comprised of communist European exiles, local union activists, street children and avant-garde artists like Frida Kahlo

In the town of Slurry, New York, post-war recession has bitten. Claire Zachanassian, improbably beautiful and impenetrably terrifying, returns to her hometown as the world's richest woman. The locals hope her arrival signals a change in their fortunes, but they soon realise that prosperity will only come at a terrible price...

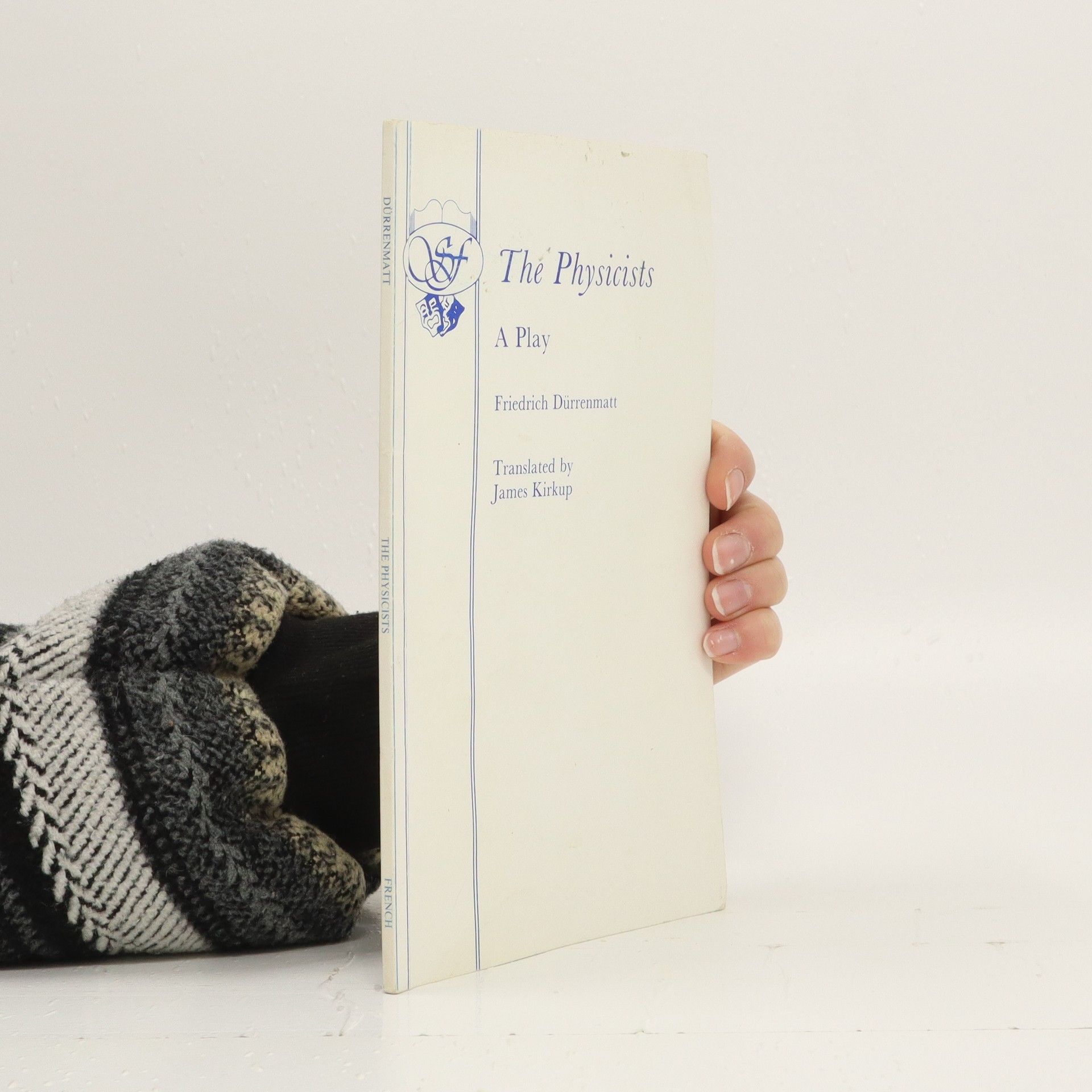

The world's greatest physicist, Johann Wilhelm Mobius, is in a madhouse, haunted by recurring visions of King Solomon. He is kept company by two other equally deluded scientists: one who thinks he is Einstein, another who believes he is Newton. It soon becomes evident, however, that these three are not as harmlessly lunatic as they appear. Are they, in fact, really mad? Or are they playing some murderous game, with the world as the stake? For Mobius has uncovered the mystery of the universe--and therefore the key to its destruction--and Einstein and Newton are vying for this secret that would enable them to rule the earth.

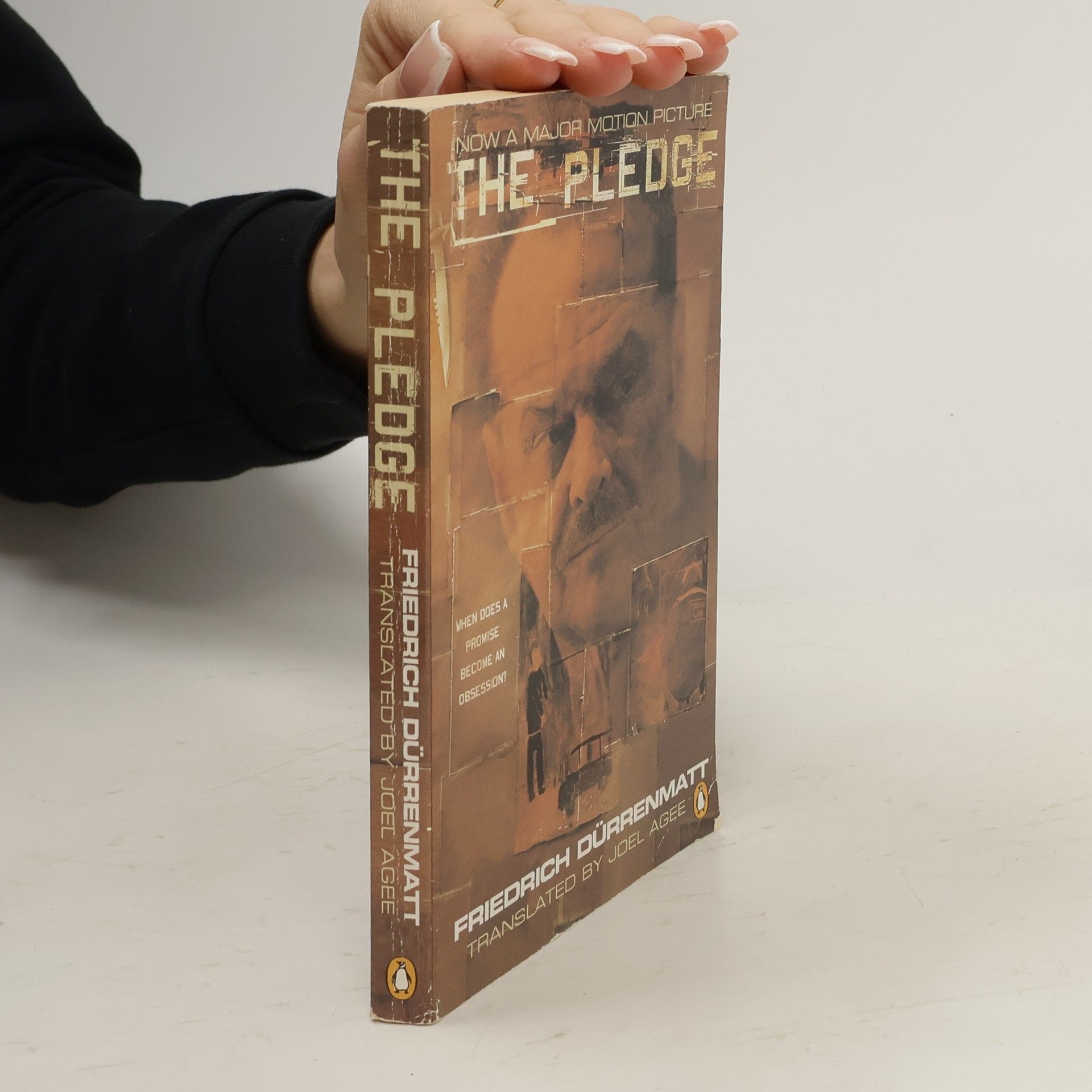

A young child has been found brutally murdered. A mother's world has been shattered forever. And a detective has made a pledge to find the killer. Now, one man's crime is about to become another man's obsession. But the detective is a man of his word. No one can stop him. And no one can save him.

This volume offers bracing new translations of two precursors to the modern detective novel by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, whose genre-bending mysteries recall the work of Alain Robbe-Grillet and anticipate the postmodern fictions of Paul Auster and other contemporary neo-noir novelists. Both mysteries follow Inspector Barlach as he moves through worlds in which the distinction between crime and justice seems to have vanished. In The Judge and His Hangman , Barlach forgoes the arrest of a murderer in order to manipulate him into killing another, more elusive criminal. And in Suspicion , Barlach pursues a former Nazi doctor by checking into his clinic with the hope of forcing him to reveal himself. The result is two thrillers that bring existential philosophy and the detective genre into dazzling convergence.

İsviçre edebiyatının çağdaş yazarlarından Dürrenmatt, kendi hayat hikayesini alışılmışın dışında kaleme almıştır. Eserleriyle yaşantıları arasındaki ilişkiyi nesnel bir gözle keşfederek ve bu bağıntıyı ön planda tutarak anlatır hayatını. Yazdığı, yazamadığı konuların hikayesidir onca hayatı. Bu nedenle otobiyografisine "Konularım" başlığını vermiştir. Eserlerinin çoğu dilimize çevrilmiş bir yazarın kendi hayatını değişik bir tarzda anlattığı bu kitap, edebiyatın niteliği sorunu üzerine de düşündürmesi bakımından değerli.

Unser Schülerarbeitsheft begleitet bei der Erschließung der Ganzschrift Der Besuch der alten Dame von Friedrich Dürrenmatt und dessen Themen. Das Unterrichtsmaterial mit abwechslungsreichen Aufgaben, Arbeitsblättern, Hilfestellungen und einer schülernahe Gestaltung mit Illustrationen fördert die Kreativität und das individuelle Lerntempo im Fach Deutsch. Einsetzbar als Arbeitsheft im Unterricht, im Homeschooling und für die private Nutzung. Das Schülerheft enthält anschauliche Illustrationen Aufgaben zur Inhalts- und Verständnissicherung Figurenkonstellation und Beziehungen Schreibanlässe mit Erschließung und Hilfestellungen (Brief, Tagebuch, innerer Monolog) Themen, Motive und Konflikte der Lektüre Glossar Die Materialien entwickeln sukzessive die Schreibkompetenz, welche auf nachvollziehbare Gedankengänge, ausformulierte innere Diskussionen sowie sprachliche Gewandtheit abzielt.