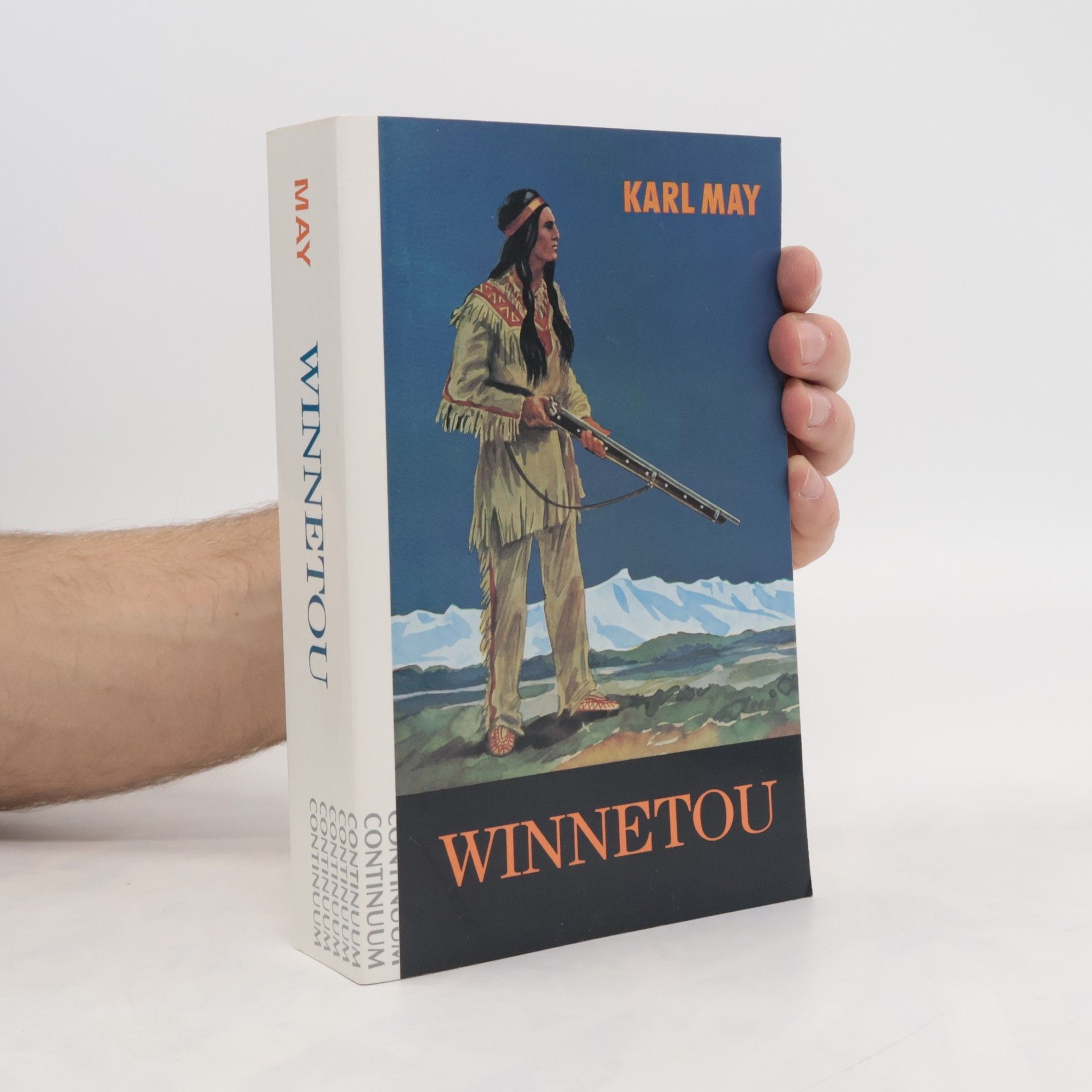

Winnetou

- 749 pages

- 27 hours of reading

Karl May's most popular work originally published in 1892 and influenced by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Winnetou is the story of a young Apache chief told by his white friend and blood-brother Old Shatterhand. The action takes place in the U.S. Southwest, in the latter half of the 1800s, where the Indian way of life is threatened by the first transcontinental railroad. Winnetou, the only Native Indian chief who could have united the various rival tribes to reach a settlement with the whites, is murdered. His tragic death foreshadows the death of his people. May's central theme here, as in much of his work, is the relationship between aggression, racism, and religious intolerance.