"Presents Newton as a wealthy, ambitious Londoner with international connections, challenging the prevailing view of Newton as a solitary, reclusive genius. A unique narrative structure based on a Hogarth's painting 'The Indian Emperor', incorporating iconographic evidence to identify Newton as a participant in aristocratic metropolitan circles. Relates Newton and his science to Britain's imperial networks and the African slave trade, exposing Britain's greatest scientific hero as a participant in global trading based on slavery"--Publisher's description

Patricia Fara Book order (chronological)

Patricia Fara is a historian of science whose work illuminates the intricate relationship between art, Enlightenment England, and the contributions of women to scientific discovery. She delves into how visual culture and societal roles have shaped the trajectory of scientific thought. Through her accessible writings and lectures, Fara brings the history of science to life for a broad audience. Based at the University of Cambridge, she explores the dynamic interplay of art and societal forces in the evolution of scientific ideas.

Erasmus Darwin

- 336 pages

- 12 hours of reading

A tour of the late eighteenth century English Enlightenment in the company of Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, who (aside from his poetry and other scientific endeavours) was expounding theories of evolution years before the birth of his more famous grandson.

A Lab of One's Own

- 352 pages

- 13 hours of reading

2018 marked the centenary not only of the Armistice but also of women gaining the vote. A Lab of One's Own commemorates both anniversaries by exploring how the War gave female scientists, doctors, and engineers unprecedented opportunities to undertake endeavours normally reserved for men.

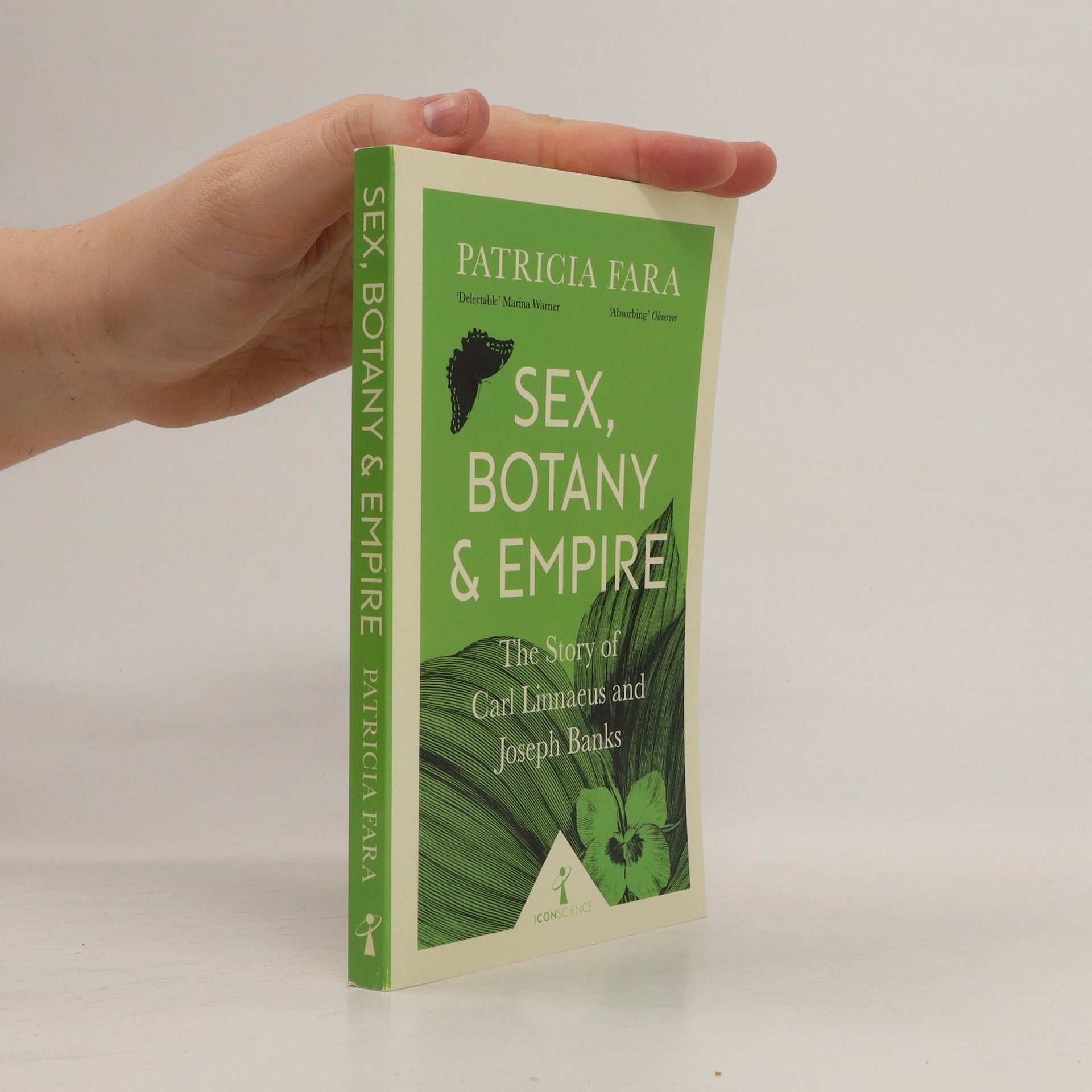

Sex, Botany and Empire

- 170 pages

- 6 hours of reading

"When the imperial explorer James Cook returned from his first voyage to Australia, scandal writers mercilessly satirised the amorous exploits of his botanist Joseph Banks, whose trousers were reportedly stolen while he was inside the tent of Queen Oberea of Tahiti. Was the pursuit of scientific truth really what drove Enlightenment science? In Sweden and Britain, both imperial powers, Banks and Carl Linneaus ruled over their own small scientific empires, promoting botanical exploration to justify the exploitation of territories, peoples and natural resources. Regarding native peoples with disdain, these two scientific emperors portrayed the Arctic North and the Pacific Ocean as uncorrupted Edens, free from the shackles of Western sexual mores. Patricia Fara reveals the existence, barely concealed under Banks' and Linnaeus' camouflage of noble Enlightenment, of the altogether more seedy drives to conquer, subdue and deflower in the name of the British Imperial state." -- Provided by publisher.

Entertainment for Angels

- 192 pages

- 7 hours of reading

Benjamin Franklin's Enlightenment world of philosophy, spectacle and electricity.

4000 Jahre Wissenschaft

- 642 pages

- 23 hours of reading

In 4000 Jahren Wissenschaft erzählt Patricia Fara die Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften neu und zeigt, wie sie von Krieg, Politik und Wirtschaft geprägt wurden. Sie enthüllt die fesselnden Geschichten hinter abstrakten Theorien und Experimenten und stellt die Forscher als echte Menschen dar, die Fehler machten und im Wettlauf um Erfolg manchmal ihre Konkurrenten behinderten. Fara führt uns durch die Jahrhunderte, von den Sumerern bis zur modernen Gentechnik und Teilchenphysik, und beleuchtet die finanziellen Interessen, Machtambitionen und verlegerischen Risiken, die die Naturwissenschaften zu einem globalen Phänomen gemacht haben. Ihre Perspektive ist umfassend und umfasst bedeutende wissenschaftliche Projekte weltweit, von China bis zum islamischen Reich, während sie auch die vertrauteren europäischen Entwicklungen von Kopernikus bis Darwin nicht aus den Augen verliert. Diese vier Jahrtausende umfassende Erzählung stellt die absolute Souveränität der Naturwissenschaft in Frage und provoziert Gedanken: Fara argumentiert, dass der Erfolg der Naturwissenschaft nicht nur auf ihrer Richtigkeit beruht, sondern auch darauf, dass Menschen behauptet haben, sie hätte recht.

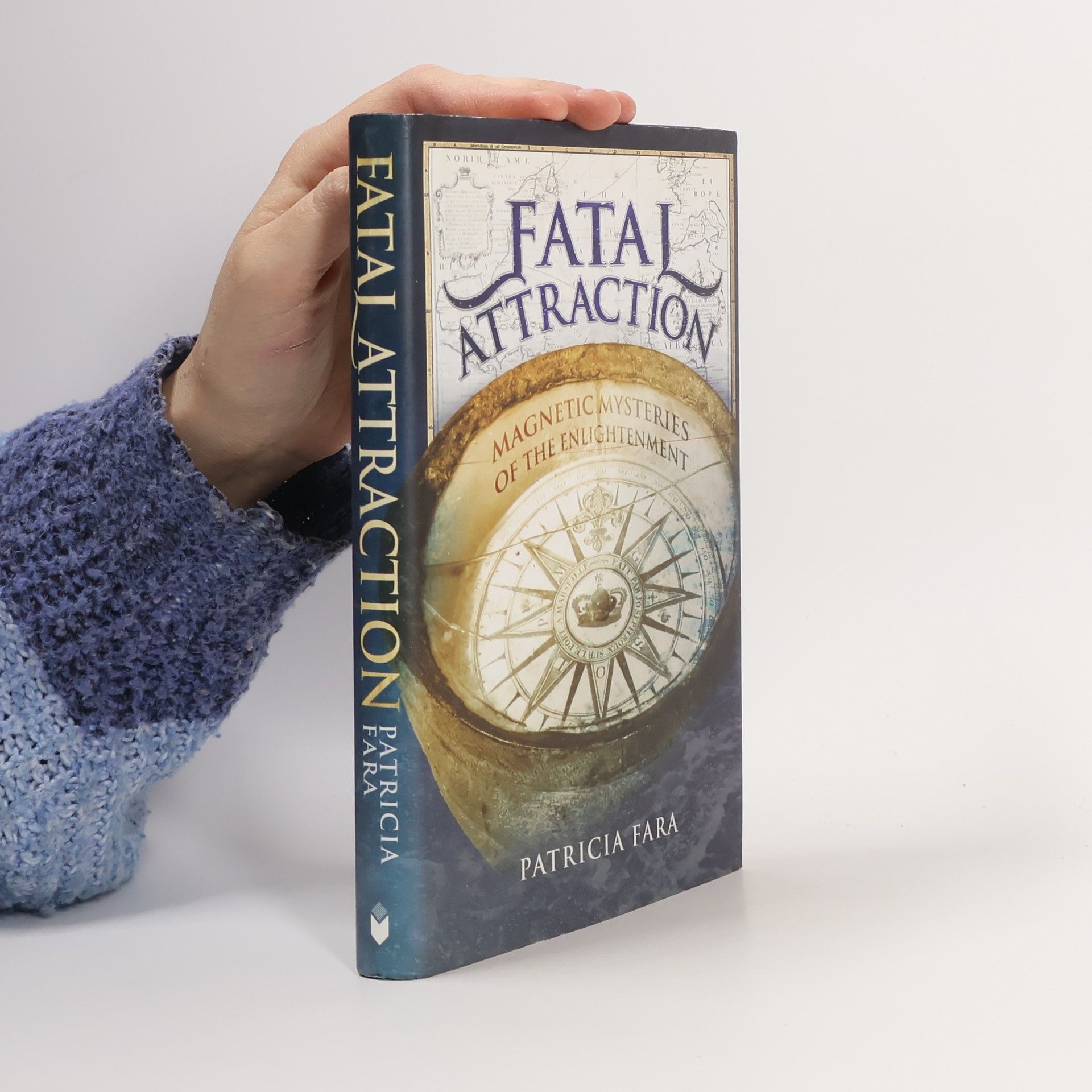

At the end of the 17th century, magnetism was a dark, mysterious force, known about since ancient Greece but still poorly understood. Tales abounded of magnets' ability to attract reluctant lovers, and magnetic expertise lay in the hands of seafarers, who had long used compasses to guide their ships. This book tells the stories of three men who were lured by nature's strangest power. Edmond Halley set out to map the Earth's magnetic patterns and improve navigation, showing how science could help England to expand her empire. Gowin Knight, a poor clergyman's son, climbed to fame and fortune by developing powerful artificial magnets used in compasses, scientific experiments and popular magic tricks. And although Franz Mesmer claimed that his 'animal magnetism', based on harnessing invisible streams of magnetic fluid, was the revolutionary medicine of the future, he was ultimately denounced as a quack. The move from magnetic mysticism to celebrating scientific rationality is a microcosm of the Enlightenment itself. In this book the author portrays the colourful protagonists of the magnetic revolution in this tumultuous and turbulent age.

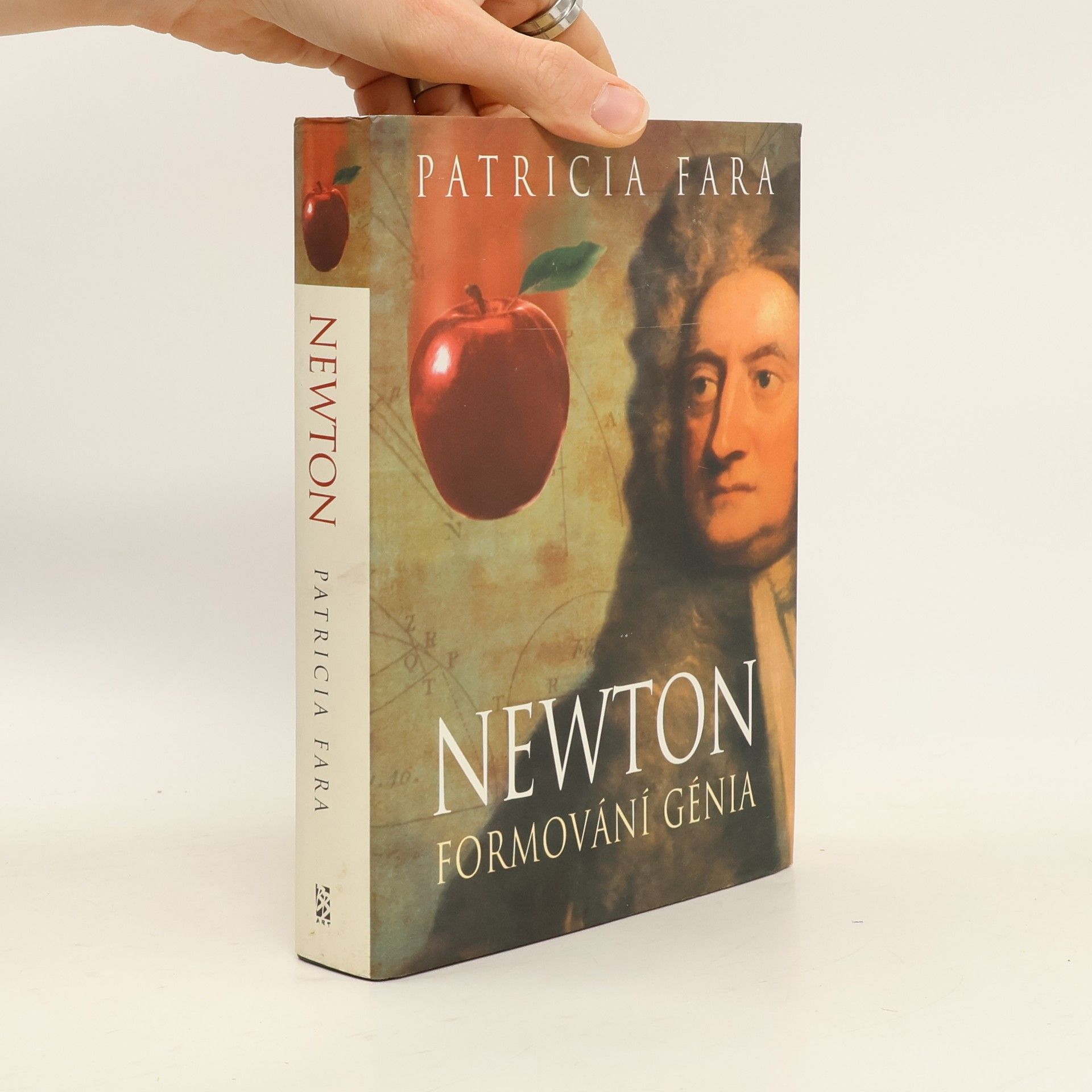

Newton – Formování génia

- 334 pages

- 12 hours of reading

Isaac Newton je oslavován jako jeden z největších vědeckých géniů světa, jako legendární hrdina, jemuž bylo dáno, aby díky pádu jablka nově zformuloval zákony přírody. Newton proslul svými revolučními myšlenkami o gravitaci a optice a stal se tak vědeckým idolem moderní doby, v níž si geniální člověk zjednává stejnou úctu, jaká byla dříve prokazována jen světcům. Ale Newton nebyl za génia uznán okamžitě. O jeho slávu se zasloužili věrní příznivci, kteří odráželi sveřepé útoky na jeho teorie a vyvraceli tvrzení, že zešílel. Tento samotářský učenec psal víc o alchymii a teologii než o světě přírody a jeho posmrtnou pověst komplikují rozpory. Tato kniha o Newtonovi zkoumá, jak byl život tohoto muže opět a opět nově vykládán, stejně jako jeho dílo. Pojednává o jeho proměně nejen v prvního vědeckého génia, ale také v lidového hrdinu. Patricia Fara vypráví o tom, jak Newtonovu novou kosmologii přijímali kladně i s kritickými výhradami odborníci, a zároveň rozebírá, proč podivínský badatel ovlivnil myšlení lidí, kteří se v jeho převratných objevech vlastně vůbec nevyznali. Rozborem výtvarných děl, poezie a prózy dospívá k tomu, jak se Newton stal kulturní veličinou, jejíž myšlenky se rozšířily po celém světě a pronikly do všech aspektů života. Newton je kniha přístupně psaná a doplněná obrazovou přílohou, v níž nalézáme podmanivé a objevné líčení proměn v postojích k našemu intelektuálnímu dědictví.

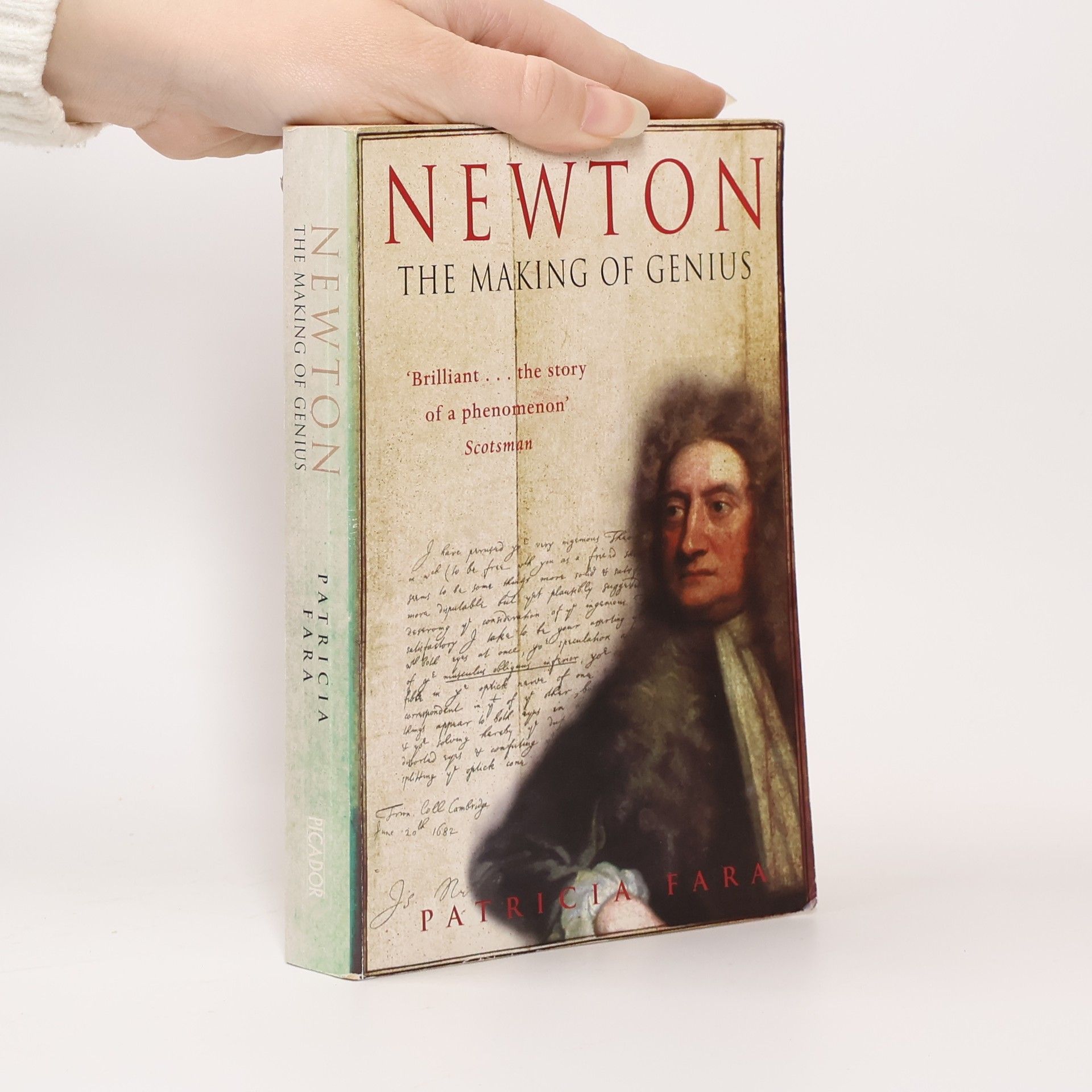

Isaac Newton is universally celebrated as a genius of science, renowned for his innovatory work on gravity and optics. Yet Newton did not always enjoy such legendary status, and his posthumous reputation has constantly changed and is riddled with contradictions.