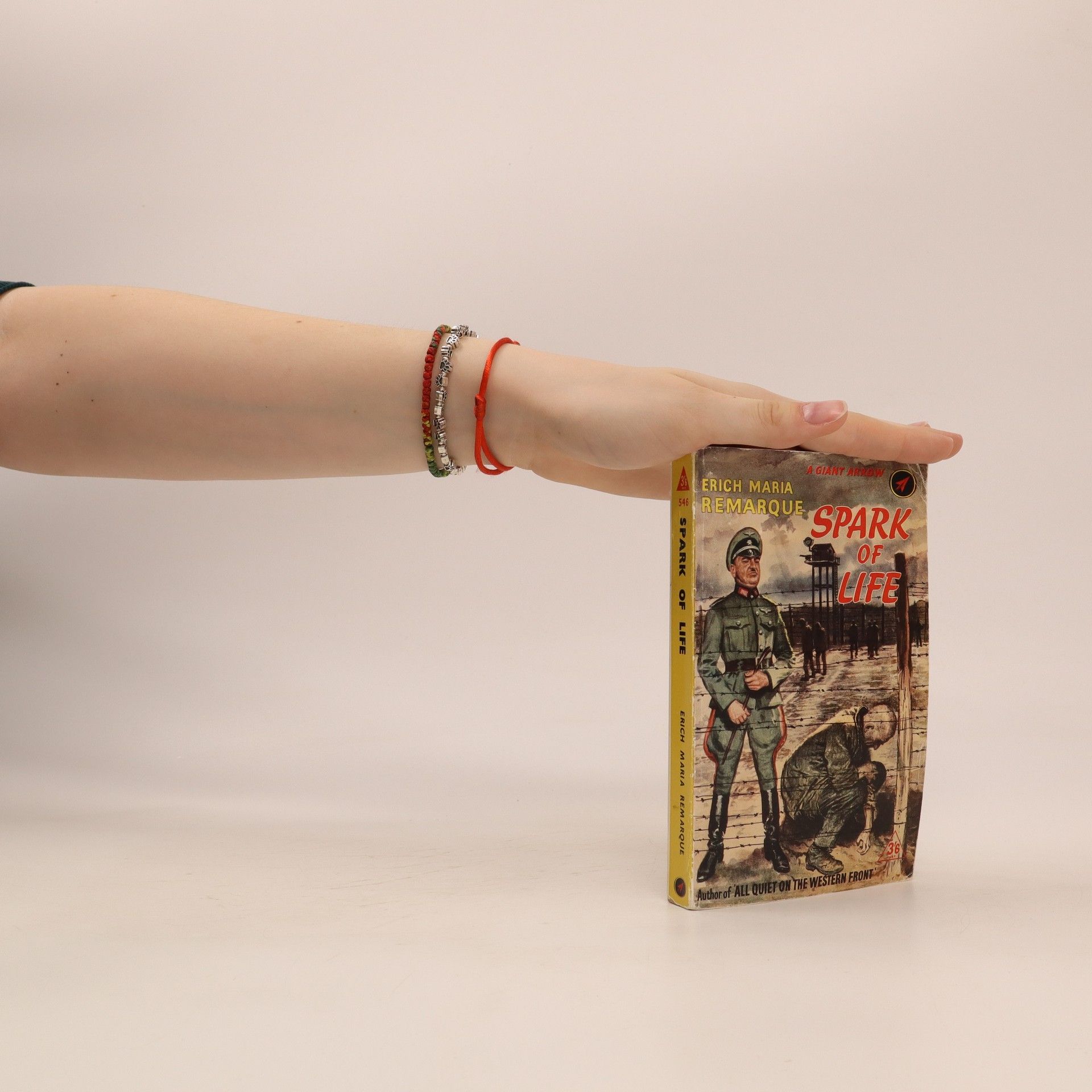

In Spark of Life, a powerful classic from the renowned author of All Quiet on the Western Front, one man’s dream of freedom inspires a valiant resistance against the Nazi war machine. For ten years, 509 has been a political prisoner in a German concentration camp, persevering in the most hellish conditions. Deathly weak, he still has his wits about him and he senses that the end of the war is near. If he and the other living corpses in his barracks can hold on for liberation—or force their own—then their suffering will not have been in vain. Now the SS who run the camp are ratcheting up the terror. But their expectations are jaded and their defenses are down. It is possible that the courageous yet terribly weak prisoners have just enough left in them to resist. And if they die fighting, they will die on their own terms, cheating the Nazis out of their devil’s contract. “The world has a great writer in Erich Maria Remarque. He is a craftsman of unquestionably first rank, a man who can bend language to his will. Whether he writes of men or of inanimate nature, his touch is sensitive, firm, and sure.”— The New York Times Book Review

Erich Maria Remarque Books

Erich Maria Remarque stands as one of the most recognized and widely read German literary figures of the twentieth century. His work is profoundly shaped by his life experiences, marked by the tumultuous history of Germany, from his youth in imperial Osnabrück through World War I and into his exile. Remarque's novels offer a critical examination of German history, consistently centering on the preservation of human dignity and humanity amidst oppression, terror, and war. His distinctive voice and the urgency of his themes continue to resonate with readers globally.

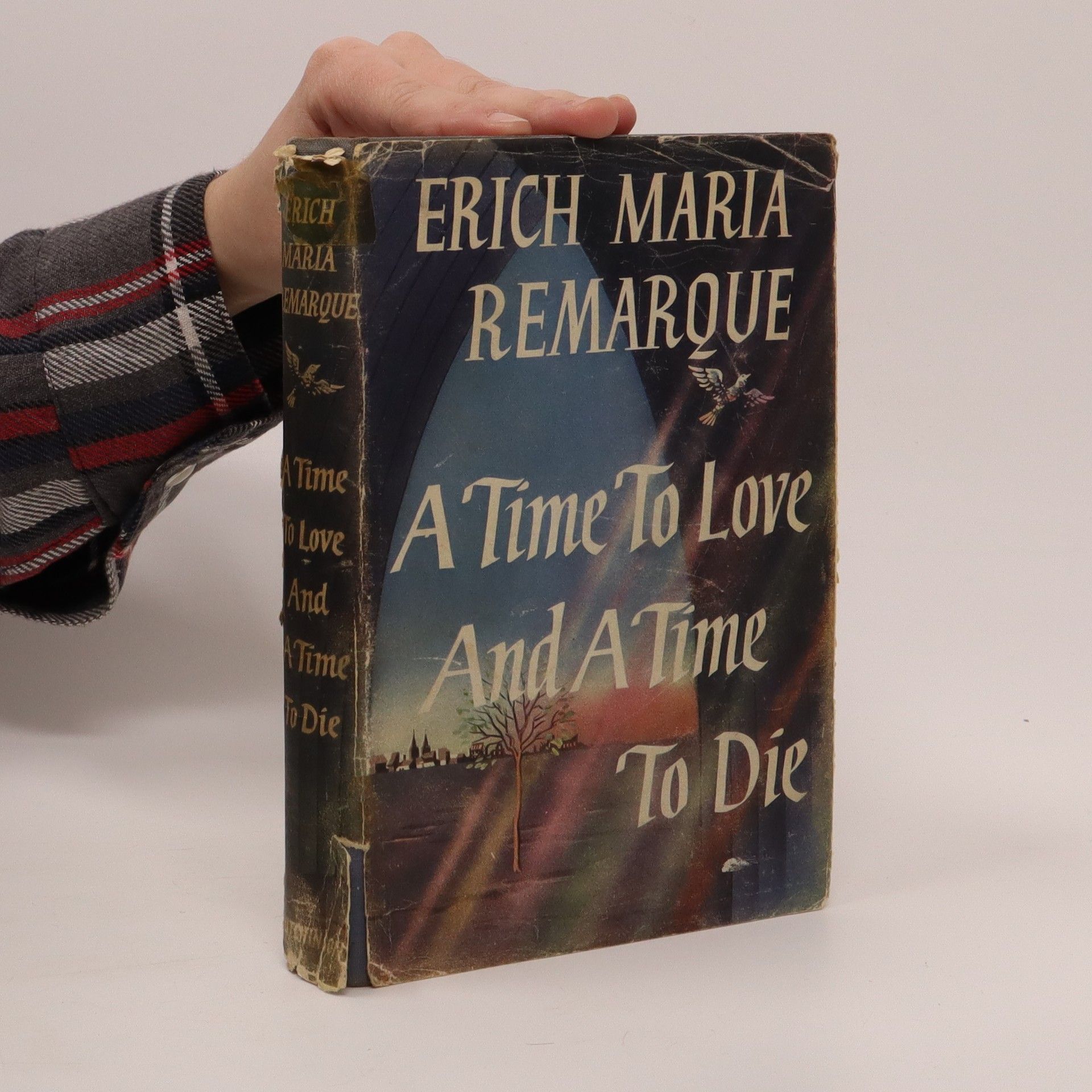

From the quintessential author of wartime Germany, A Time to Love and a Time to Die echoes the harrowing insights of his masterpiece All Quiet on the Western Front. After two years at the Russian front, Ernst Graeber finally receives three weeks’ leave. But since leaves have been canceled before, he decides not to write his parents, fearing he would just raise their hopes. Then, when Graeber arrives home, he finds his house bombed to ruin and his parents nowhere in sight. Nobody knows if they are dead or alive. As his leave draws to a close, Graeber reaches out to Elisabeth, a childhood friend. Like him, she is imprisoned in a world she did not create. But in a time of war, love seems a world away. And sometimes, temporary comfort can lead to something unexpected and redeeming.

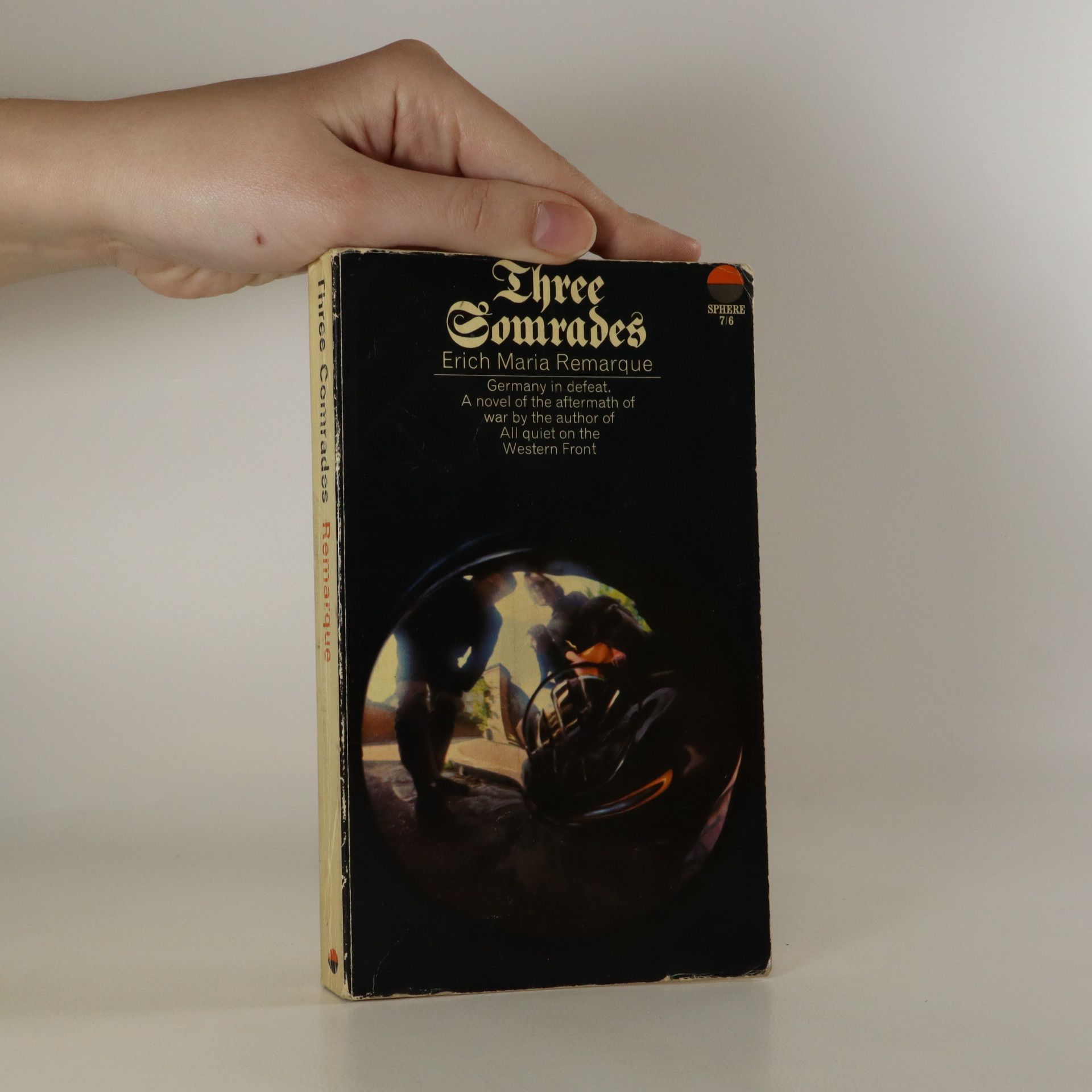

The year is 1928. On the outskirts of a large German city, three young men are earning a thin and precarious living. Fully armed young storm troopers swagger in the streets. Restlessness, poverty, and violence are everywhere. For these three, friendship is the only refuge from the chaos around them. Then the youngest of them falls in love, and brings into the group a young woman who will become a comrade as well, as they are all tested in ways they can never have imagined. . . .Written with the same overwhelming simplicity and directness that made All Quiet on the Western Front a classic, Three Comrades portrays the greatness of the human spirit, manifested through characters who must find the inner resources to live in a world they did not make, but must endure.

It is 1939. Despite a law banning him from performing surgery, Ravic--a German doctor and refugee living in Paris--has been treating some of the city's most elite citizens for two years on the behalf of two less-than-skillful French physicians. Forbidden to return to his own country, and dodging the everyday dangers of jail and deportation, Ravic manages to hang on--all the while searching for the Nazi who tortured him back in Germany. And though he's given up on the possibility of love, life has a curious way of taking a turn for the romantic, even during the worst of times

From the author of the masterpiece All Quiet on the Western Front, The Black Obelisk is a classic novel of the troubling aftermath of World War I in Germany. A hardened young veteran from the First World War, Ludwig now works for a monument company, selling stone markers to the survivors of deceased loved ones. Though ambivalent about his job, he suspects there's more to life than earning a living off other people's misfortunes. A self-professed poet, Ludwig soon senses a growing change in his fatherland, a brutality brought upon it by inflation. When he falls in love with the beautiful but troubled Isabelle, Ludwig hopes he has found a soul who will offer him salvation--who will free him from his obsession to find meaning in a war-torn world. But there comes a time in every man's life when he must choose to live--despite the prevailing thread of history horrifically repeating itself. The world has a great writer in Erich Maria Remarque. He is a craftsman of unquestionably first rank, a man who can bend language to his will. Whether he writes of men or of inanimate nature, his touch is sensitive, firm, and sure.--The New York Times Book Review

ARCH OF TRIUMPHIt is 1939. Despite a law banning him from performing surgery, Ravic—a German doctor and refugee living in Paris—has been treating some of the city's most elite citizens for two years on the behalf of two less-than-skillful French physicians.Forbidden to return to his own country, and dodging the everyday dangers of jail and deportation, Ravic manages to hang on—all the while searching for the Nazi who tortured him back in Germany. And though he's given up on the possibility of love, life has a curious way of taking a turn for the romantic, even during the worst of times. . . .

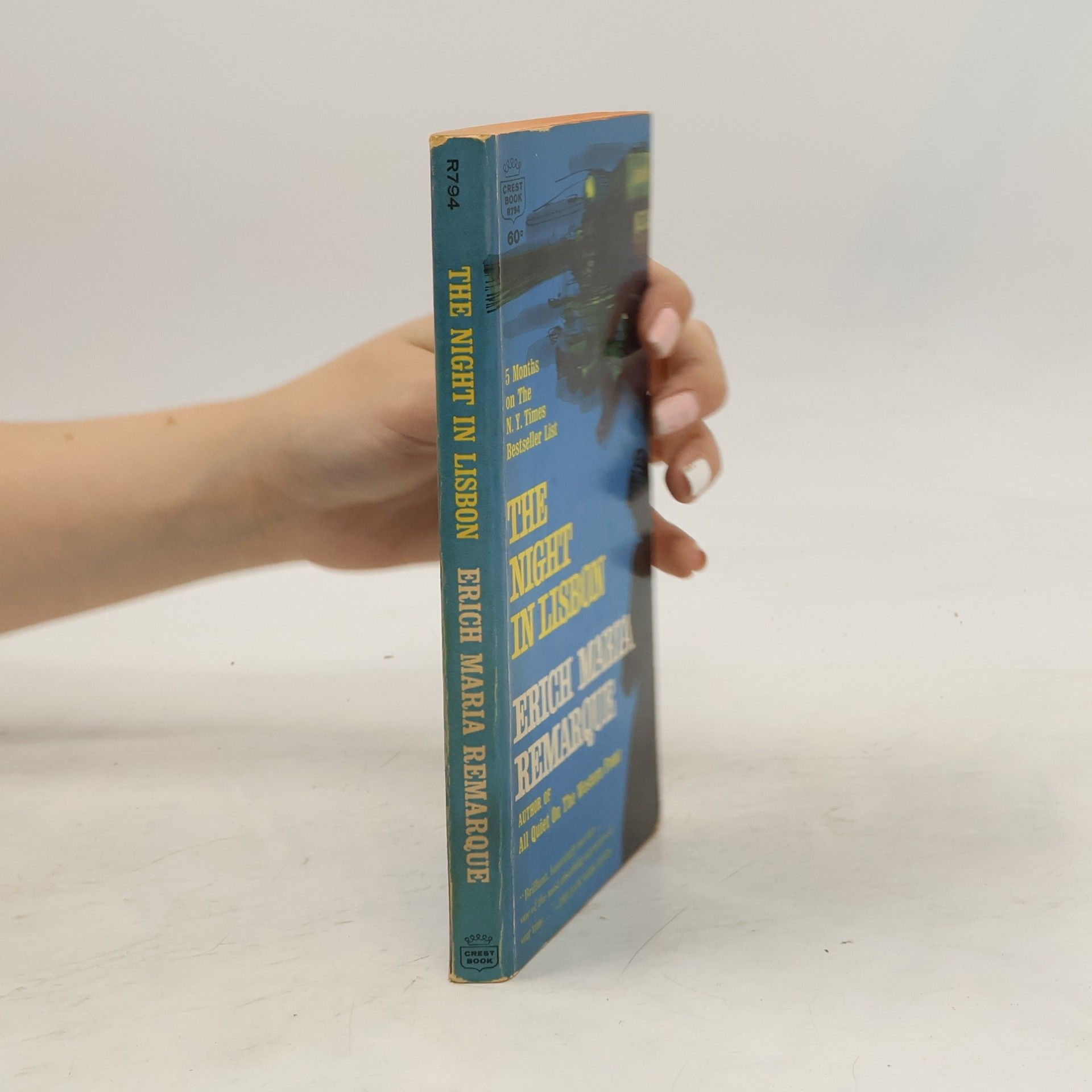

History and fate collide as the Nazis rise to power in The Night in Lisbon, a classic tale of survival from the renowned author of All Quiet on the Western Front. With the world slowly sliding into war, it is crucial that enemies of the Reich flee Europe at once. But so many routes are closed, and so much money is needed. Then one night in Lisbon, as a poor young refugee gazes hungrily at a boat bound for America, a stranger approaches him with two tickets and a story to tell. It is a harrowing tale of bravery and butchery, daring and death, in which the price of love is beyond measure and the legacy of evil is infinite. As the refugee listens spellbound to the desperate teller, in a matter of hours the two form a unique and unshakable bond—one that will last all their lives.

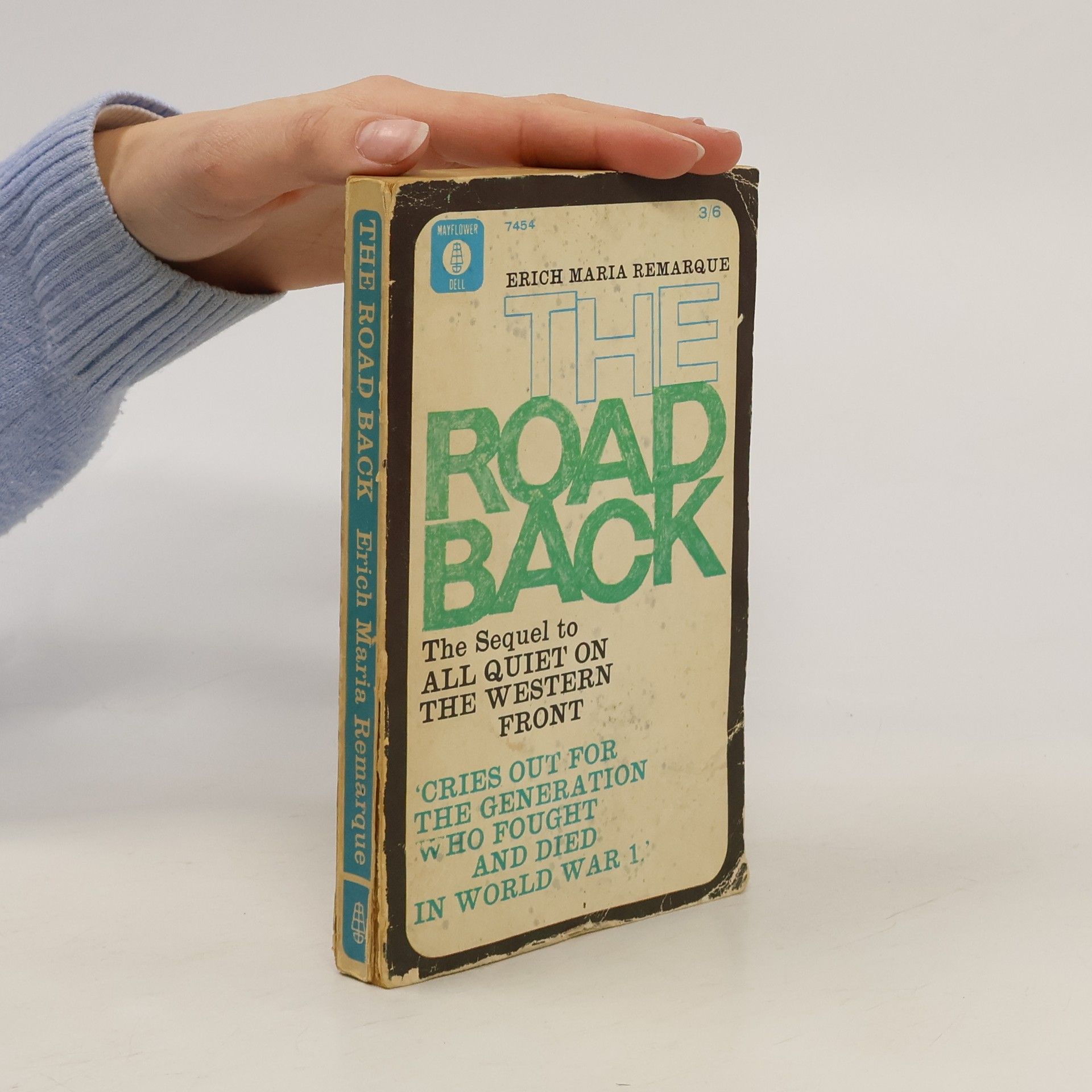

The Road Back: A Novel (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- 264 pages

- 10 hours of reading

Set in the aftermath of World War I, this novel explores the gradual healing and restoration of Europe. It delves into the struggles and resilience of individuals as they navigate the challenges of rebuilding their lives and societies. As a sequel to All Quiet on the Western Front, it continues to address themes of loss, recovery, and the impact of war on the human spirit, providing a poignant reflection on the journey towards peace and normalcy in a war-torn continent.

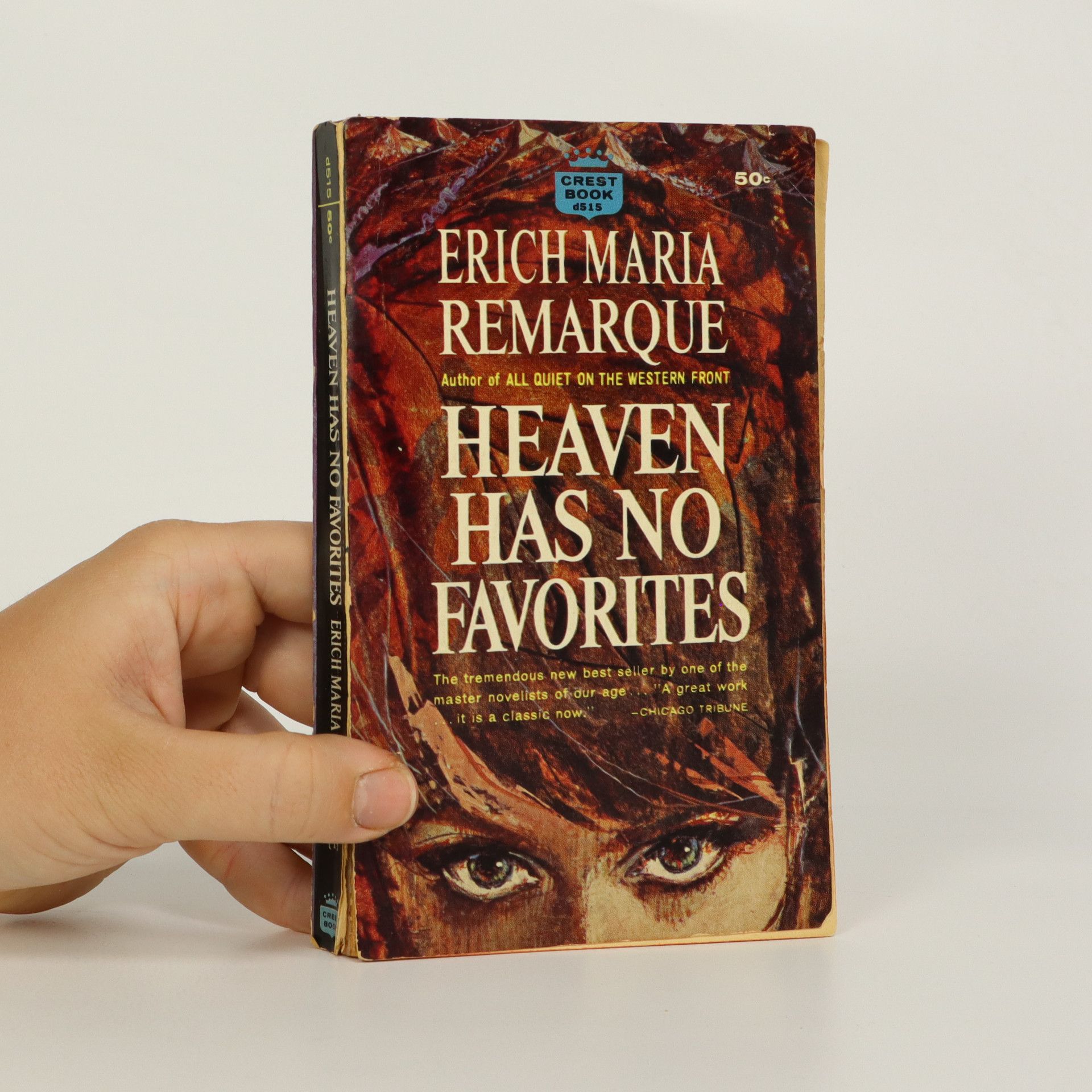

From one of the twentieth century’s master novelists, the author of the classic All Quiet on the Western Front, comes Heaven Has No Favorites, a bittersweet story of unconventional love that sweeps across Europe. Lillian is charming, beautiful . . . and slowly dying of consumption. But she doesn’t wish to end her days in a hospital in the Alps. She wants to see Paris again, then Venice—to live frivolously for as long as possible. She might die on the road, she might not, but before she goes, she wants a chance at life. Clerfayt, a race-car driver, tempts fate every time he’s behind the wheel. A man with no illusions about chance, he is powerfully drawn to a woman who can look death in the eye and laugh. Together, he and Lillian make an unusual pair, living only for the moment, without regard for the future. It’s a perfect arrangement—until one of them begins to fall in love.

The sequel to All Quiet on the Western Front, one of the most powerful novels of the First World War and a twentieth-century classic.