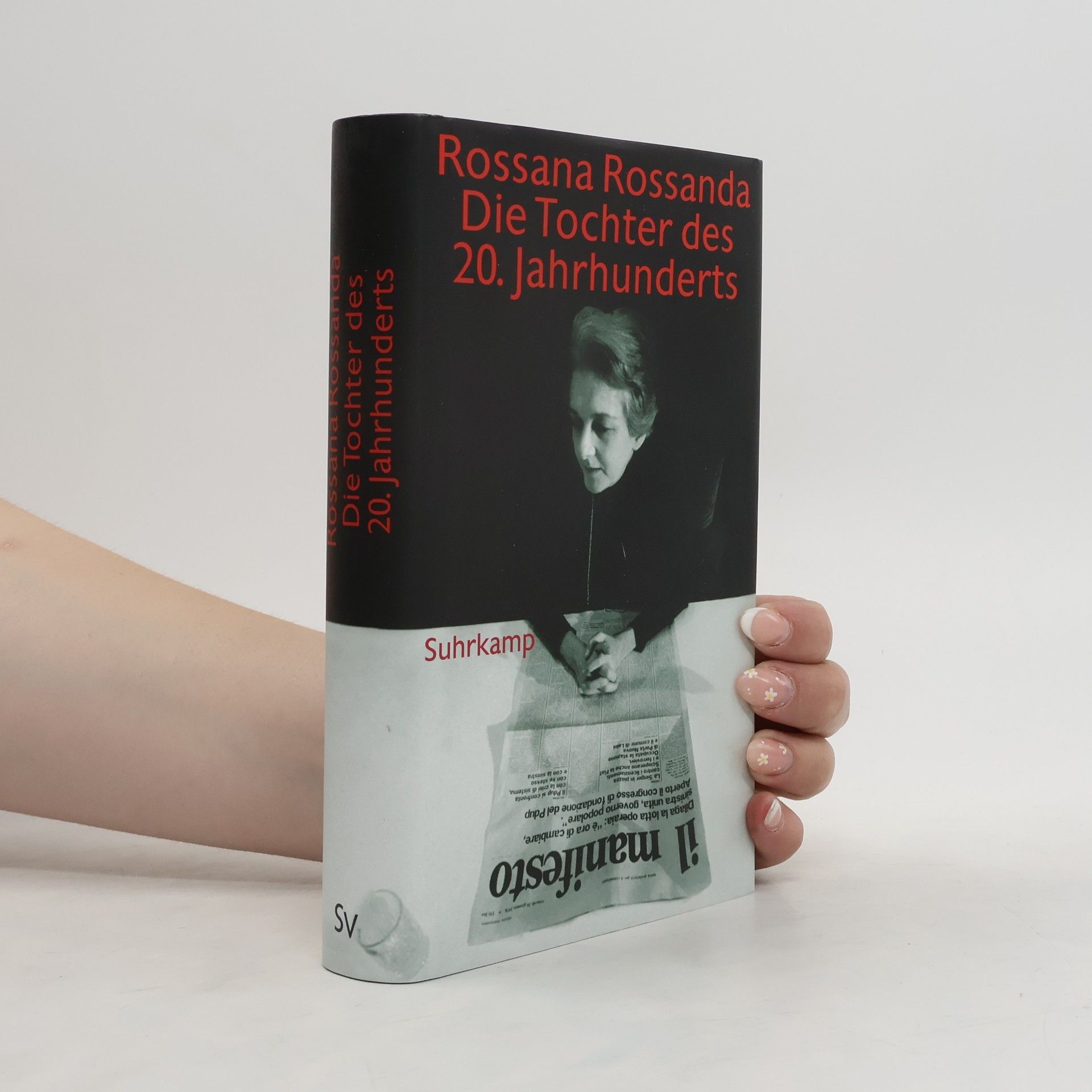

The Comrade from Milan

- 384 pages

- 14 hours of reading

A striking account of the European Left in the twentieth century by one of its main protagonists

Rossanda was a significant intellectual figure whose work grappled with the complexities of political thought and social movements. Her writings explored the philosophical underpinnings of youthful rebellion and challenged established political orthodoxies. She possessed a sharp analytical mind, evident in her ability to dissect ideological conflicts and advocate for reform from within and outside traditional party structures. Rossanda's contributions offered a unique perspective on the intersection of ideology, activism, and societal change.

A striking account of the European Left in the twentieth century by one of its main protagonists

A collection of essays on the mysteries of the body from one of Italy’s leading postwar communist intellectuals. Politician, translator, and journalist Rossana Rossanda was the most important female left-wing intellectual in post-war Italy. Central to the Italian Communist Party’s cultural wing during the 1950s and ’60s, she left an indelible mark on the life of the mind. The essays in this volume, however, bring together Rossanda’s reflections on the body—how it ages, how it is gendered, what it means to examine one’s own body. The product of a decades-long dialogue with the Italian women’s movement (above all with Lea Melandri, a vital feminist writer who provides an afterword to the current volume), these essays represent an honest and raw meeting between communist and feminist thought. Ranging from reflections on her own hands through to Chinese cinema, from figures such as the Russian cross-dressing soldier Nadezhda Durova to the Jacobin revolutionary Theroigne de Mericourt, here we see Rossanda’s fierce intellect and extraordinary breadth of knowledge applied to the body as a central question of human experience.

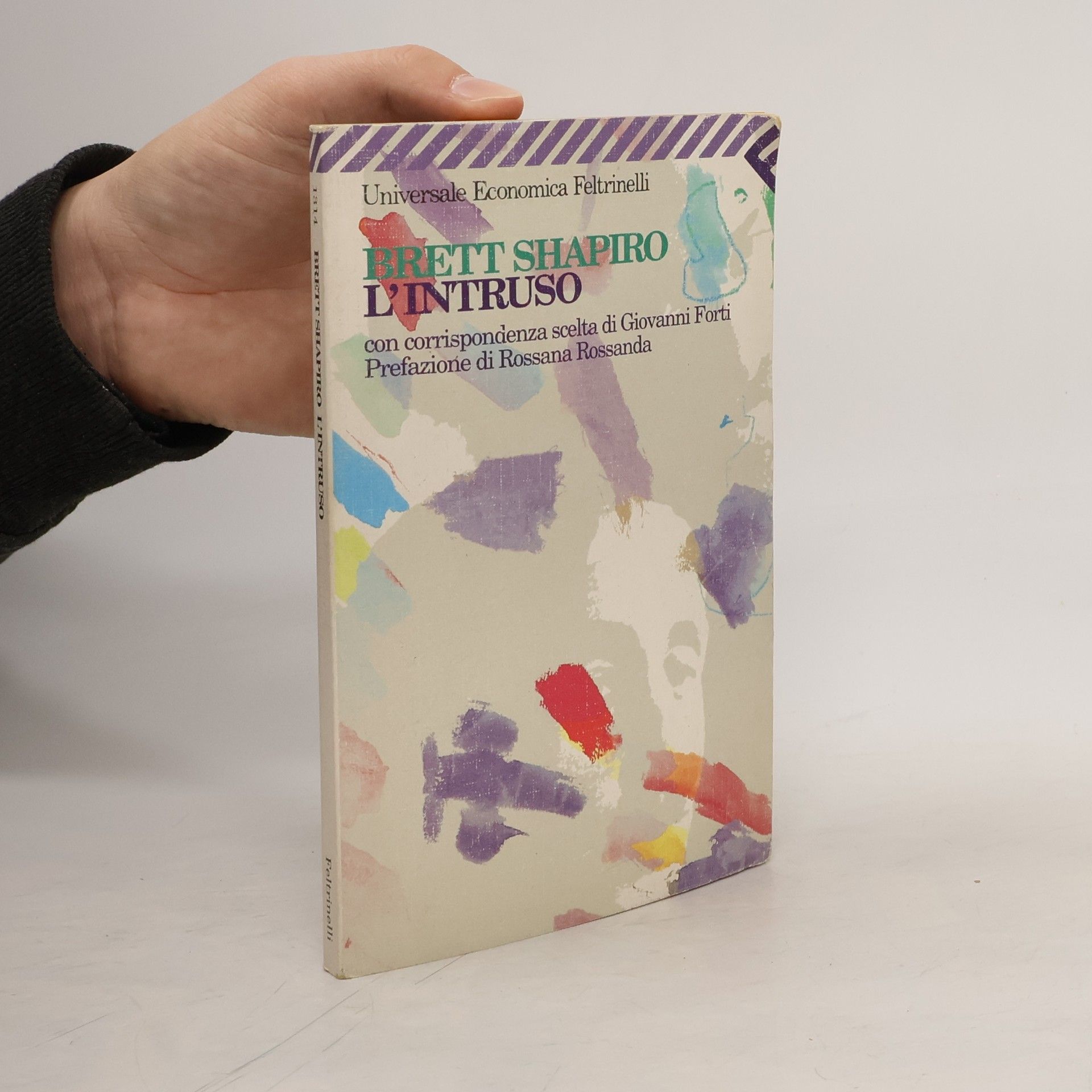

Brett Shapiro, scrittore e giornalista statunitense, incontra nel giugno del 1990 Giovanni Forti, corrispondente dell'Espresso, che vive a New York con il figlio adolescente. Fra i due uomini nasce una relazione d'amore e dopo tre mesi decidono di vivere insieme con il bambino adottato da Brett; l'unione sarà formalizzata con un matrimonio secondo il rito ebraico riformato. Nel libro, le voci di entrambi descrivono la vicenda di questa famiglia provocatoria e non tradizionale in cui si inserisce quasi subito un intruso: l'Aids. Intercalando alla narrazione alcune lettere di Giovanni, Shapiro ripercorre la loro storia con l'Aids. L'ultimo capitolo è un diario scritto da Brett durante le ultime settimane di vita di Giovanni.

«Questo non è un libro di storia. È quel che mi rimanda la memoria quando colgo lo sguardo dubbioso di chi mi è attorno: perché sei stata comunista? perché dici di esserlo? che intendi? senza un partito, senza cariche, accanto a un giornale che non è più tuo? è una illusione cui ti aggrappi, per ostinazione, per ossificazione? Ogni tanto qualcuno mi ferma con gentilezza: "Lei è stata un mito!" Ma chi vuol essere un mito? Non io. I miti sono una proiezione altrui, io non c'entro. Mi imbarazza. Non sono onorevolmente inchiodata in una lapide, fuori del mondo e del tempo. Resto alle prese con tutti e due. Ma la domanda mi interpella. La vicenda del comunismo e dei comunisti del Novecento è finita così malamente che è impossibile non porsela. Che è stato essere un comunista in Italia dal 1943? Comunista come membro di un partito, non solo come un momento di coscienza interiore con il quale si può sempre cavarsela: "In questo o in quello non c'entro". Comincio dall'interrogare me. Senza consultare né libri né documenti ma non senza dubbi. Dopo oltre mezzo secolo attraversato correndo, inciampando, ricominciando a correre con qualche livido in più, la memoria è reumatica. Non l'ho coltivata, ne conosco l'indulgenza e le trappole. Anche quelle di darle una forma. Ma memoria e forma sono anch'esse un fatto tra i fatti. Né meno né più».

»Dies ist kein Geschichtsbuch. Es ist das, was in meinem Gedächtnis auftaucht, wenn ich den zweifelnden Blick der Menschen um mich herum auffange: Warum bist du Kommunistin gewesen? Warum sagst du, du bist es noch? Was meinst du damit? Ohne eine Partei, ohne Ämter, an der Seite einer Zeitung, die dir nicht mehr gehört? Ist es eine Illusion, an die du dich klammerst, aus Sturheit, aus Altersstarrsinn? Ab und zu hält mich jemand freundlich an: >Sie waren ein Mythos!< Doch wer will schon ein Mythos sein? … Die Sache des Kommunismus und der Kommunisten im 20. Jahrhundert hat so kläglich geendet, daß man sich unbedingt damit auseinandersetzen muß. Was bedeutete es, in Italien ab 1943 Kommunist zu sein? Als Parteimitglied, nicht nur aus innerer Überzeugung, bei der man sich immer herausreden kann: >Mit diesem oder jenem habe ich nichts zu tun.< Ich beginne, indem ich mich selbst befrage. Ohne Bücher oder Dokumente zu konsultieren, aber nicht ohne manchen Zweifel.«