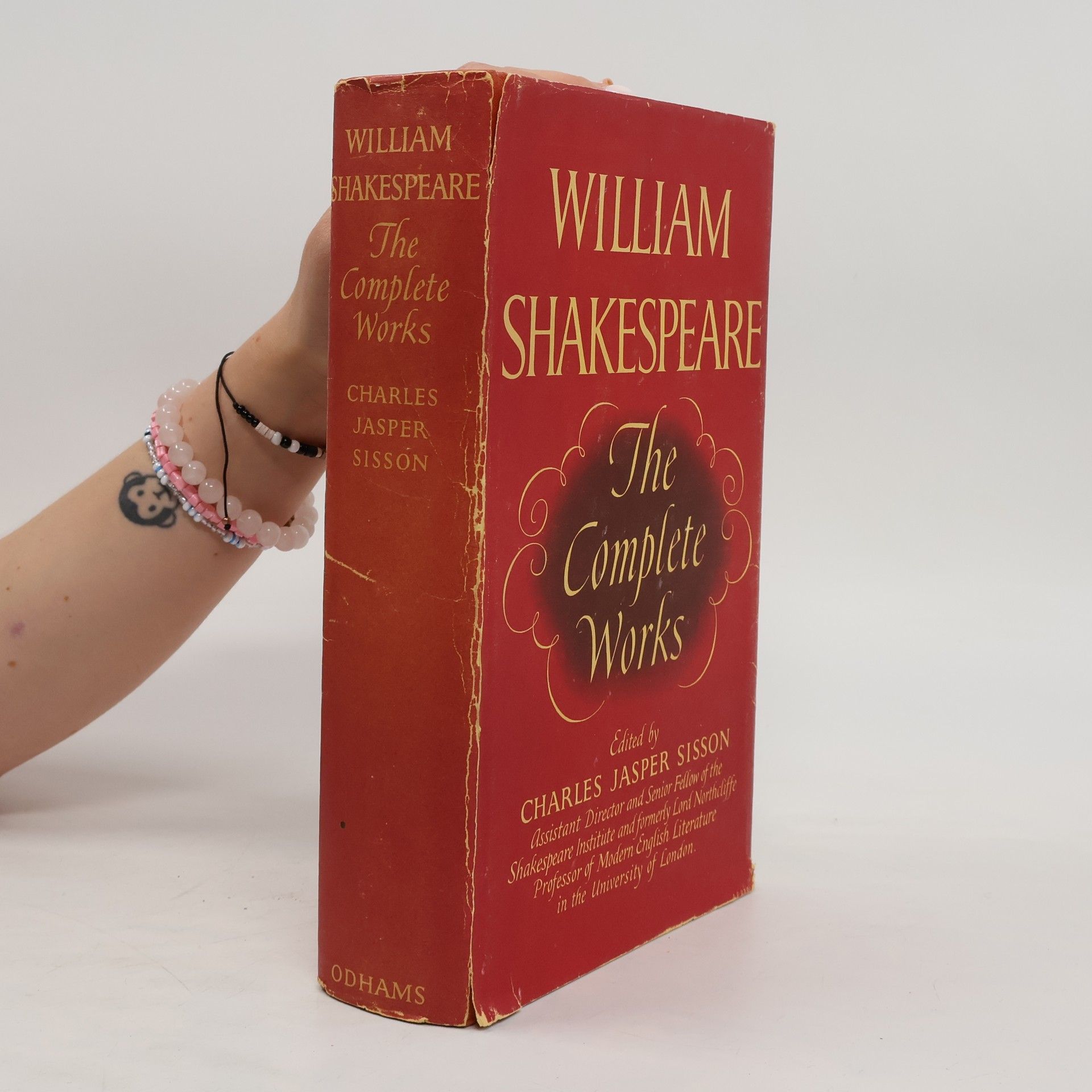

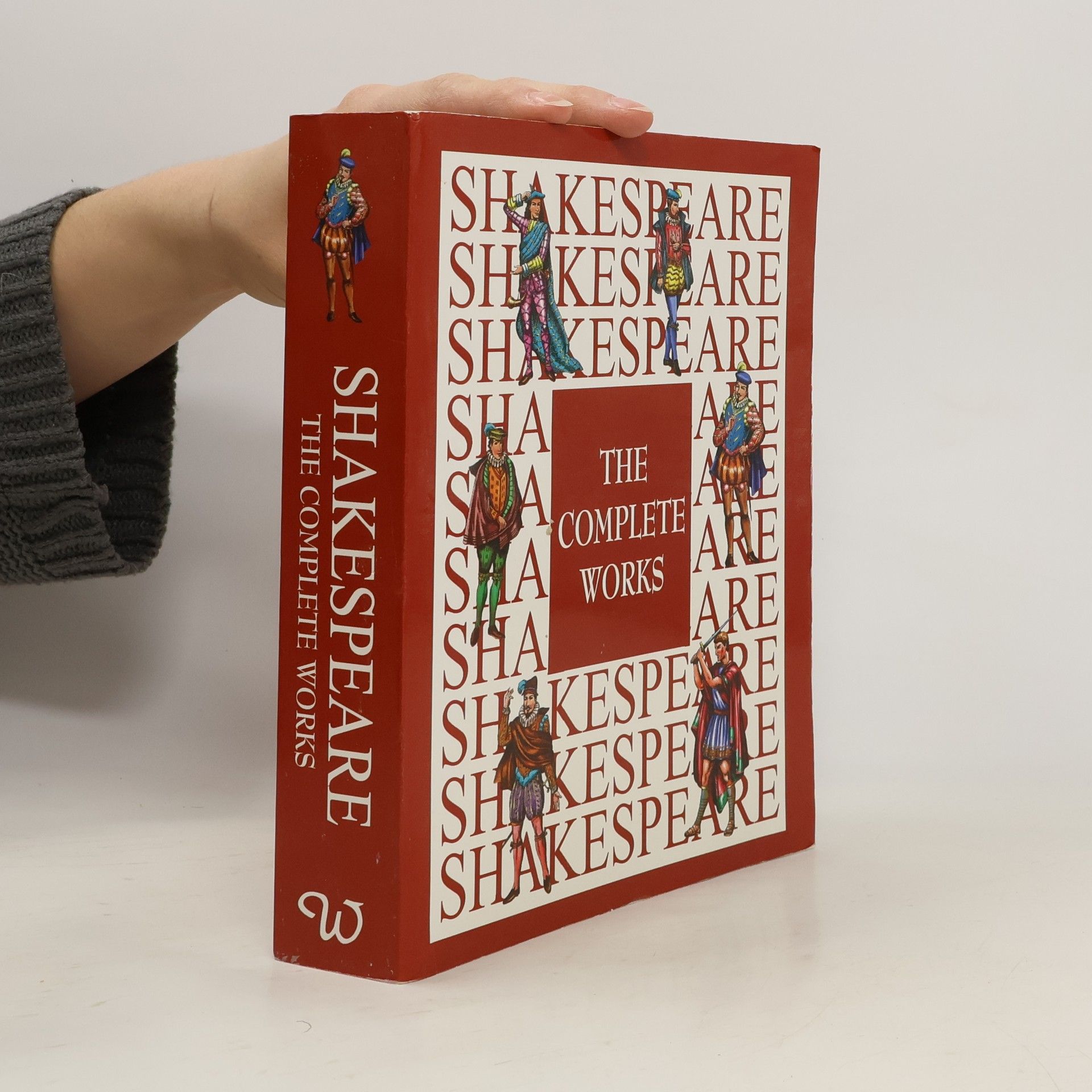

The Complete Works

- 1031 pages

- 37 hours of reading

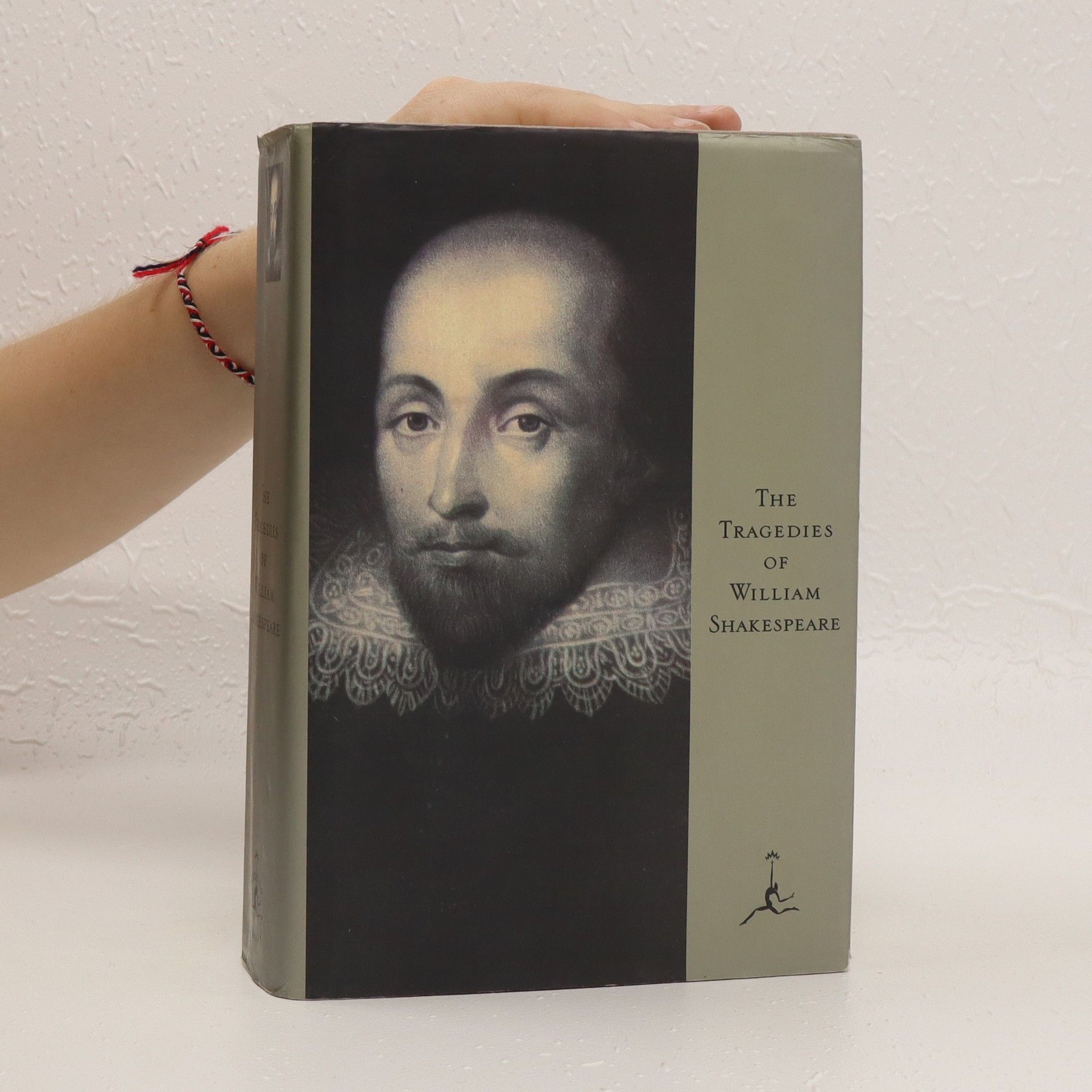

Shakespeare requires no introduction -- he is "the Bard," the most imposing playwright and storyteller in the English language. William Shakespeare (1564-1616) is acknowledged as the greatest dramatist of all time. He excels in plot, poetry and wit, and his talent encompasses the great tragedies of Hamlet, King Lear, Othello and Macbeth as well as the moving history plays and the comedies such as A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Taming of the Shrew and As You Like It with their magical combination of humour, ribaldry and tenderness. This volume presents all the plays in chronological order in which they were written. It also includes Shakespeare's Sonnets, as well as his longer poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. This complete and unabridged edition contains every word that Shakespeare wrote — all 37 tragedies, comedies, and histories, plus the sonnets. You'll find such classics as The Tempest, Much Ado About Nothing and The Taming of the Shrew. Shakespeare's "Complete Works" is a must-have for anyone who loves the English language -- his writing was unparalleled, and even his lesser plays are a cut above the rest. Not only a pleasure to read, but an altogether new experience in reading!!!